Intensity Delta

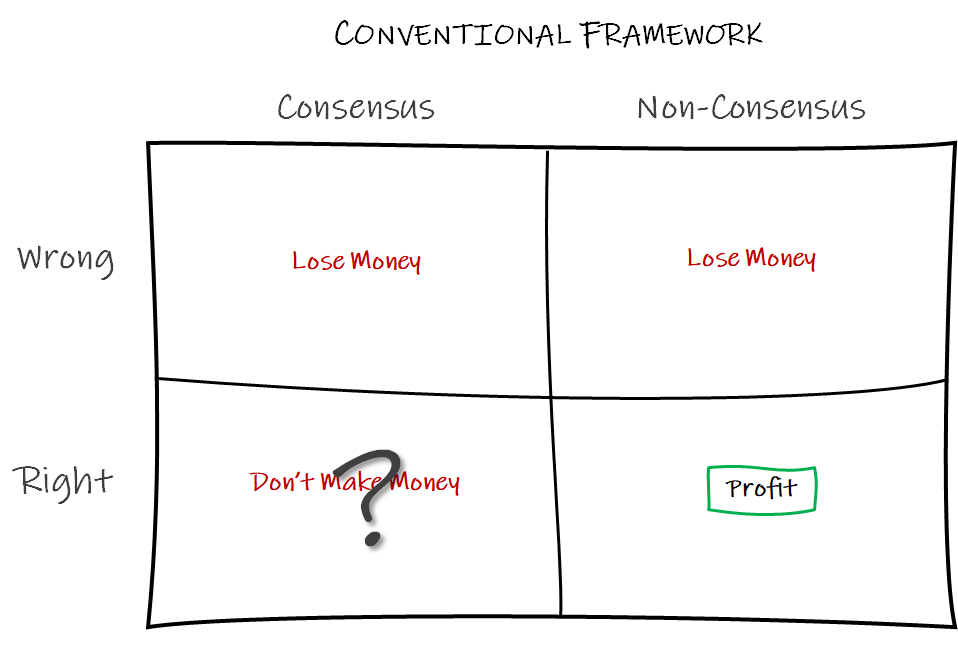

There is a common saying in investing that it is not enough to be right; you need to be contrarian and right. Having a consensus opinion, even if it ends up being right, supposedly means that the asset is efficiently priced and excess profits are arbitraged away.

I disagree. You can have the same consensus directional view on something and still make (a lot of) money. In fact, I posit that right plus consensus is not only where most returns come from, it is also where the best returns come from.

The reason for this is the intensity delta - a view that something will be occur at a greater magnitude than others believe and/or occur over a longer period of time.

Liberty explains this concept well:

“Most of my investing alpha doesn’t come from being directionally contrarian, but from having a different intensity than the consensus, even if in the same direction. Many investors are obsessed with the contrarian bets where the consensus is wrong. I find that most of my bets are “the market thinks this is a 8.5/10 business, and I think it’s a 9.2/10 business” or that “growth will decline at rate X, and I think it’ll be rate 0.9X”, and the delta between those two beliefs is enough to create a very nice return, especially over multi-year periods.”

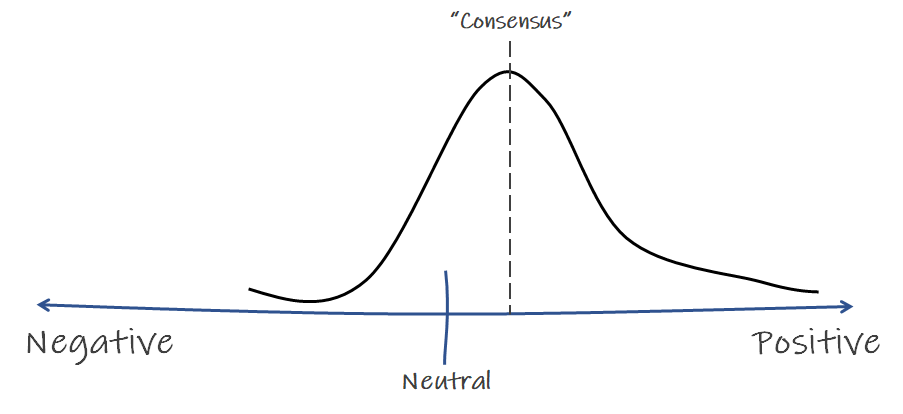

The problem with the conventional 2x2 framework is that “consensus” is often misinterpreted as a binary directional call (positive or negative), when it is actually a distribution on a continuum:

In this example, the consensus is already positive, but if you are more positive than the market-clearing consensus point, than you should profit if the distribution curve shifts in your direction.

Of course, you still need to be ‘right’, or else none of this matters. But assuming you are, the idea here is that a different intensity in views is more important, easier, repeatable, and more scalable than focusing on only binary contrarian ideas.

There are two ways the intensity delta can manifest:

1) You are more positive or negative than consensus

This can be a specific short term event or catalyst such as an earnings report or product launch, which is a game that most market participants play, or it can be more general (“this is a better business than most people believe”).

2) Your view will persist over a longer period of time

This is a distinct point because reality is more than a single continuum; the market price of a security is a function of many dimensions, and time is one of the most powerful. You can think a business is as good as most people do today, but the intensity delta can come from your view persisting over a much longer period than anyone else is willing or able to price in today.

Insights & Related Thoughts

1) Intensity delta > contrarian

Looking back on my investment career, most of my best decisions were “the market thinks this is a good business, but I think it is even better”, and not “everyone hates this stock but they’re wrong”. There are a few reasons why the former is better:

-

The market is already primed to like the stock. Current investors just need to continue to like it (easy to do since already convinced) or like it more. New investors are easily persuaded since it is easy to find external validation. It is more attractive and validating to show up to a club with a line-up out the door than a house party with two people and a cat.

-

Momentum flywheel. A good business tends to do better over time (launch better products, acquire more customers, improve retention, raise more capital, attract better employees, etc.), which has a compounding effect, whereas a bad business has the opposite effect.

So why is there so much focus on contrarianism in the investment world? There is certainly some ego involved and it is intellectually more satisfying to be right when others are wrong. There is also a belief that if the consensus flips from positive to negative or the reverse, there will be big swings in the stock. That sounds great in theory, and certainly does happen, but it is not only difficult to find contrarian ideas, it often takes more than you expect for the consensus view to flip (narratives are difficult to change, there is often a large overhang of underwater investors looking to get out “when it comes back”, etc.).

2) It doesn’t take much of a delta between your view and consensus to generate significant returns.

It can be difficult to measure or quantify the intensity delta, but it doesn’t take a large one to generate significant alpha if your view is correct.

Drawing this on the continuum graphic would start to get complicated, but stock price returns is not a linear relationship to intensity delta narrowing; it is exponential because small changes in business results and shifts in the distribution curve of views can translate into large share price moves.

I don’t think I fully grasped this early on in my career. When discussing a potential investment, I would often ask “Yes, but who doesn’t already know that?”, which is the right question, but sometimes I would see it as a false dichotomy and not appreciate how much the intensity of the ‘knowing’ can matter, even if the delta seems small.

3) The more positive/negative that consensus is, the greater the risk.

The further away from neutral that the distribution curve of views already is, the harder it is realize an intensity delta, and consequently, the greater the risk if/when there is revision to the neutral.

It can be easy to fool yourself by falling in love with a stock that everyone already loves with the same or more intensity, when, in reality, expectations are so extreme that there isn’t any delta left. Any hiccup can result in large negative returns because returns are are not linear in the negative direction either. The higher the consensus, the greater the risk.

4) Time is the best intensity delta of all

Of the three main buckets of public market investment “edge”, time is the most durable (the other two edges being informational and analytical, both of which are extremely competitive and perishable). But time is also the hardest intensity delta to capitalize on for the vast majority of market participants.

For institutional investors, returns are measured and benchmarked at least quarterly or monthly for LPs/investors, and available - at least internally - in real time. There is constant pressure to outperform every period. A bad year, let alone an even longer time period of underperformance, can be highly detrimental to the fund’s ability to retain and attract capital, especially early in its life. While institutional investors, in general, may have a better ability to identify long term trends and companies that will do well, short term market dynamics and nuances of managing a fund often get in the way from capitalizing on it.

Retail investors also find it difficult to benefit from long term vision. Countless studies and actual data show that trying to time the market and trading actually reduce returns for the average investor - yet they do so anyways. Behavioral economics explains a lot of this through concepts such as loss aversion, overconfidence, status quo bias, and temporal discounting (favoring near term outcomes).

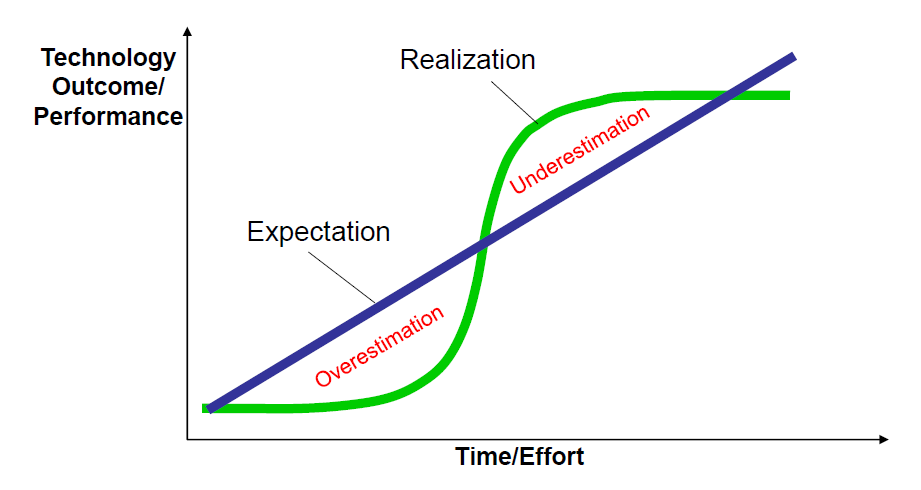

The other thing that makes a time delta difficult is that you actually have to be right, which gets harder for longer time periods. The further out the prediction, the greater the distribution of possible outcomes. But, if you are right, and have the patience and discipline to wait, the upside is also of another magnitude because people tend to overestimate progress in the short term and underestimate it in the long term.

Source: 'Technology Strategy' course, Prof. Kapoor, 2017, Wharton