Sales & Marketing is Capex

Modern financial statements are artifacts of an era in which traditional businesses needed to keep track of finances. Revenue and expenses; cash in and cash out. While no set accounting standard could capture every business’s economic reality even a hundred years ago, the basic properties worked well for most companies.

Today, financial statements are even less one-size-fits-all as companies have a myriad of business models, complicated corporate structures, ever-burgeoning tax and accounting rules, and fundamentally new ways of doing business. The standard three financial statements - income, balance sheet, and cash flow - are still very useful, but they don’t come anywhere close to enabling a complete understanding of a company’s economic and financial picture.

The result is that almost every company today reports “non-GAAP” operating metrics and some version of “adjusted” earnings. Meanwhile, the entire sell-side research industry and an army of buy-side analysts spend virtually all of their time analyzing financial statements and modifying them in ways that can help them more accurately view the business and make investment decisions. Not to mention the accountants, lawyers, media, and vendors that each play their own part in this complex system that all starts with those three little financial statements issued by companies four times a year and ends with adjustment after adjustment and literally hundreds of pages of footnotes.

The point is: there is a need to analyze individual companies and sectors in a way that accurately captures the unique economic reality of the business. And most often, that looks very different than standard financial statements.

Case in point, and the subject of this essay: SaaS business models today should be viewed much differently than traditional businesses. In particular, sales & marketing should be considered a capital expenditure, not an expense.

This actually generalizes more broadly - any business where customers are “acquired” can and should be viewed this way.

Why does this matter? S&M as capex better captures the revenue-generating asset of the business (customers) on the balance sheet, is a more accurate view of the company’s actual profitability, enables more robust analysis, improves predictability, and allows for more accurate valuation.

Let’s dive in:

- The Current Way

- Why SaaS Businesses Are Different

- What Does This Look Like and Implications

- Conclusions

The Current Way

Financial statements were designed for prototypical businesses such as a manufacturer that buys equipment to create goods that are then sold.

The equipment is a large, upfront cost, which has a useful life of many years. It is an asset that enables revenue to be generated. As such, it makes sense for the cost of the equipment to be spread out over multiple years to align with revenue. On the financial statements, the equipment purchase goes on the balance sheet as an asset (- cash / + asset), and it is depreciated over its useful life. That depreciation hits the income statement each period as a non-cash expense.

This is one reason why the income statement is usually materially different than cash flow - to be a more accurate representation of the business fundamentals and profitability.

The issue is that the narrow scope of what can be capitalized doesn’t transfer well to other types of business models such as SaaS.

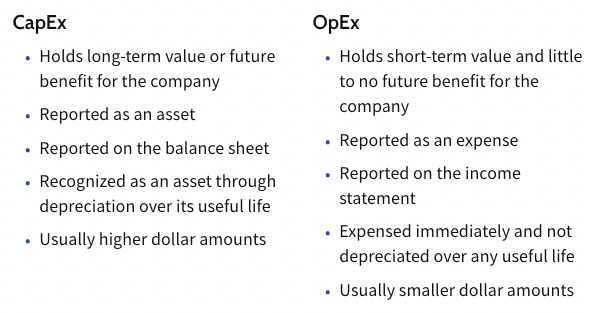

Before we get into SaaS, let’s level set on a couple definitions:

Capital Expenditure (Capex):

In terms of accounting, an expense is considered to be CapEx when the asset is a newly purchased capital asset or an investment that has a life of more than one year, or which improves the useful life of an existing capital asset.

Operating Expense (Opex):

Operating expenses are shorter-term expenses required to meet the ongoing operational costs of running a business.

The fundamental differences can be summed up thusly:

For the manufacturer example, it is clear that the equipment is capex, and the other costs (such as G&A and S&M) are opex.

We’ll come back to these definitions in a bit.

Why SaaS Businesses Are Different

SaaS businesses - or really any subscription business - are materially different from the manufacturer example above.

Notably, there are essentially no large up-front or ongoing capital costs. The product is software that is continually developed by engineers, which is G&A (or R&D1). Instead, the largest cost is typically sales & marketing. As an example, Hubspot, a $17B market cap company, has cumulatively spent over $2.4B on sales & marketing since 2010 including $650M (50% of revenue!) in 2021, and very little on typical capital assets such as PP&E (only $96M is on the balance sheet).

The other difference in SaaS is that the relationship with customers is subscription-based2. It is contractual and recurring revenue for an ongoing service, not one-off transactions for physical goods. When a subscription business acquires(!) a customer, it doesn’t have to win that customer again.

Acquired customers then pay recurring revenue to use the product over a continuous period of time until they churn for whatever reason.

Thus, the fundamentals of this type of business can be distilled to:

- How much does it cost to acquire a customer

- How much revenue is generated from the customer before it churns

- What does it cost to provide the ongoing service

I’m not reinventing anything here specifically about customer acquisition costs (CAC) or customer lifetime value (LTV). In fact, customer economics is exactly what is applicable here.

But what I am arguing is that this can apply at an even deeper level, where customer economics become company economics, right down to the financial statements.

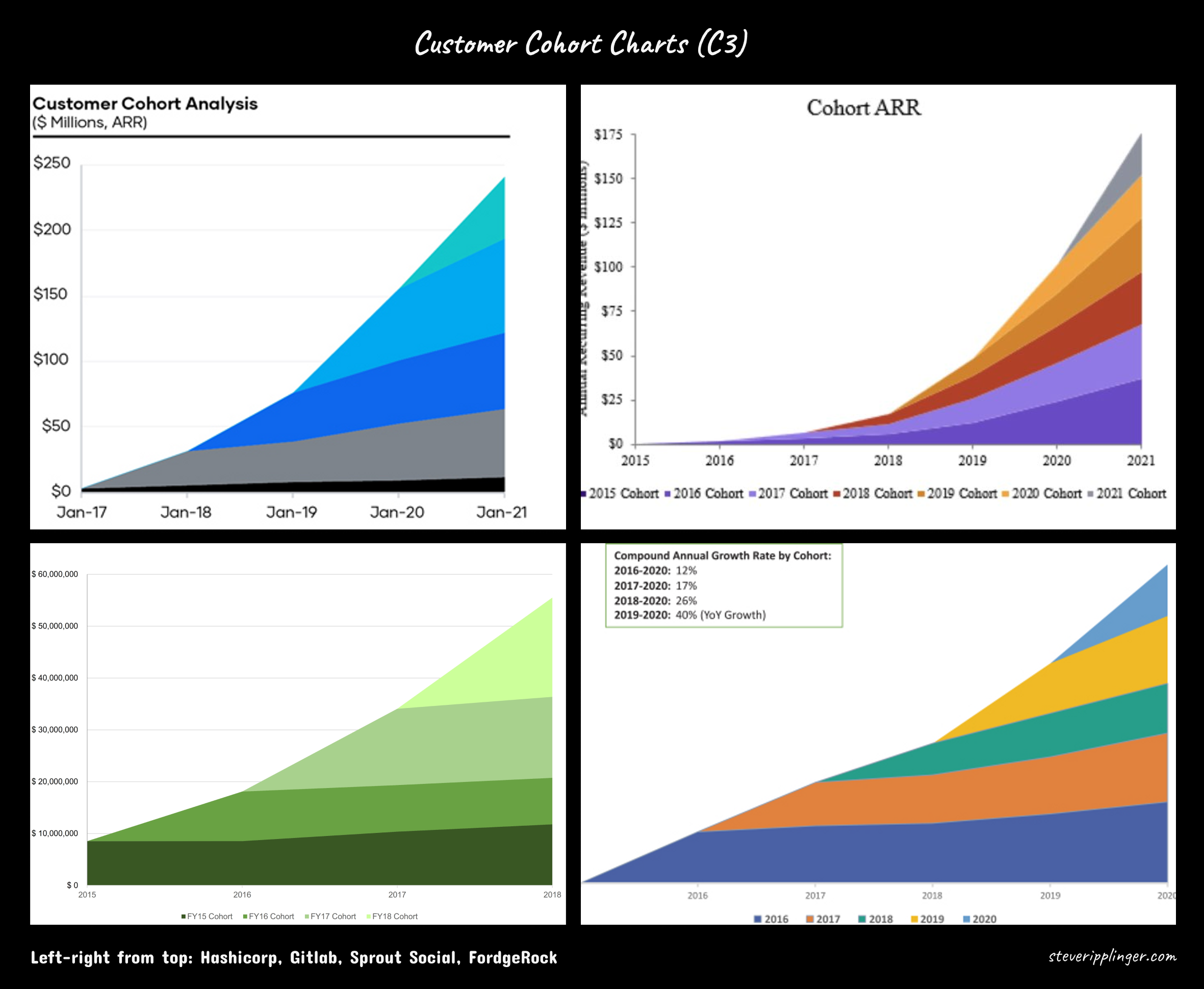

The customer-cohort-chart, which more and more companies are starting to publish3, is the best visual of this line of thinking. The “C3” chart buckets cohorts of customers based on when they were acquired, and shows revenue over time by cohort.

This perspective is infinitely more informative of a business than bucketing all customers as one and just showing total revenue each period.

In any given period, money is spent on sales and marketing to acquire a cohort of customers, that cohort of customers will have a long lifetime, active customers per cohort will naturally decline over time, and there is ongoing revenue generated from the cohort (in the best cases, increasing over time and more than offsetting churn).

These customer cohorts then stack on top of each other and are the sources of revenue in any given period.

New sales & marketing expenditures are thus an investment in new customers that will generate revenue in the future.

On the income statement, however, sales & marketing in a period is always fully expensed, despite being only directly applicable to the small portion of revenue generated from new customers, and despite leaving nothing left to match with the future revenue profile of those customers. And all of the CAC for prior cohorts that are still generating revenue has been expensed long ago. The revenue-expense matching principle is grossly violated here.

The result is a giant distortion in how profitability is presented for SaaS companies, especially if the company is growing rapidly, which is often the case.

Before delving into this a bit more, let’s go back to the definitions:

Capital Expenditure (Capex):

In terms of accounting, an expense is considered to be CapEx when the asset is a newly purchased capital asset or an investment that has a life of more than one year, or which improves the useful life of an existing capital asset.

Operating Expense (Opex):

Operating expenses are shorter-term expenses required to meet the ongoing operational costs of running a business.

Based on the dynamics of SaaS business models discussed above and these definitions, sales and marketing costs used to acquire customers should be a capital expenditure! CAC is clearly an investment in a long-term asset (customers) that has a life of more than one year, not a short-term expense to run the operations of the business with no future value.

Note: I’m using S&M and CAC a bit interchangeably throughout, but to be clear, not all sales & marketing costs should be considered CAC and capitalized4 - just those expenditures that can be reasonably attributed to new customer acquisition.

What Does This Look Like and Implications

Sounds like an investment banking interview question (”walk me through how $10 of depreciation flows through the financial statements…”).

So let’s do that. What would happen if sales and marketing were capex?

CAC-Adjusted Financial Statements

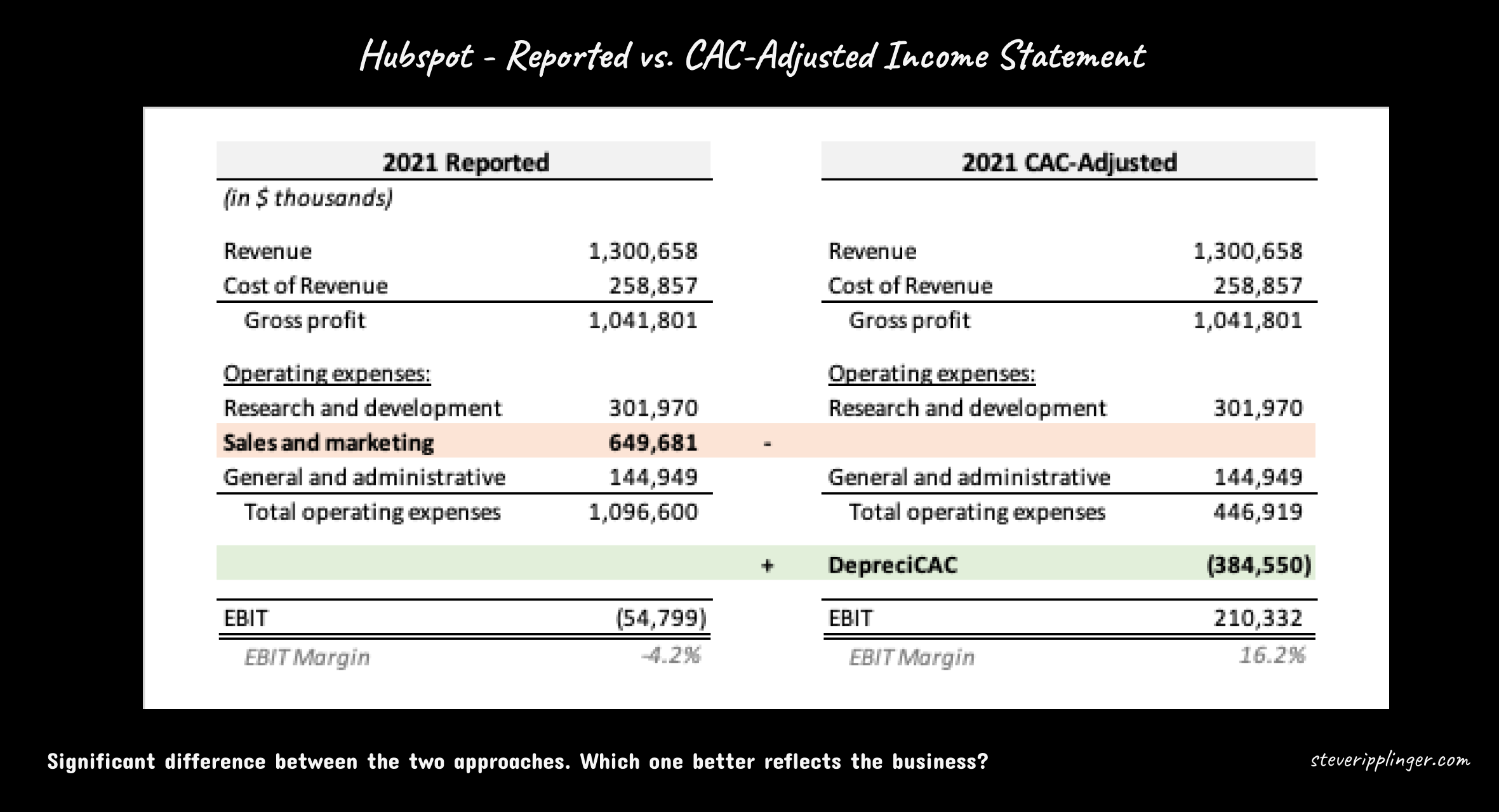

I’ll use Hubspot as an example since it has a long history as a public SaaS company.

To implement CAC-adjusted financial statements, we first take reported S&M, and move it to the balance sheet as an asset - let’s call it “assetCAC.”

Then depreciate each cohort’s assetCAC over time according to some schedule that reasonably aligns with customer lifetimes. Let’s keep it simple for Hubspot and use 5-year straight-line, but this could be any method that approximates cohort survival curves while still being practical. Instead of S&M on the income statement, there is now “depreciCAC.”

On the cash flow statement, S&M is no longer included in Cash Flow from Operations - it is its own line item in Cash Flow from Investing Activities, which we can call “CACex.”

For Hubspot, here is the difference between the traditional way S&M is reported on the income statement and the depreciCAC way with S&M fully capitalized5 and depreciated over 5 years:

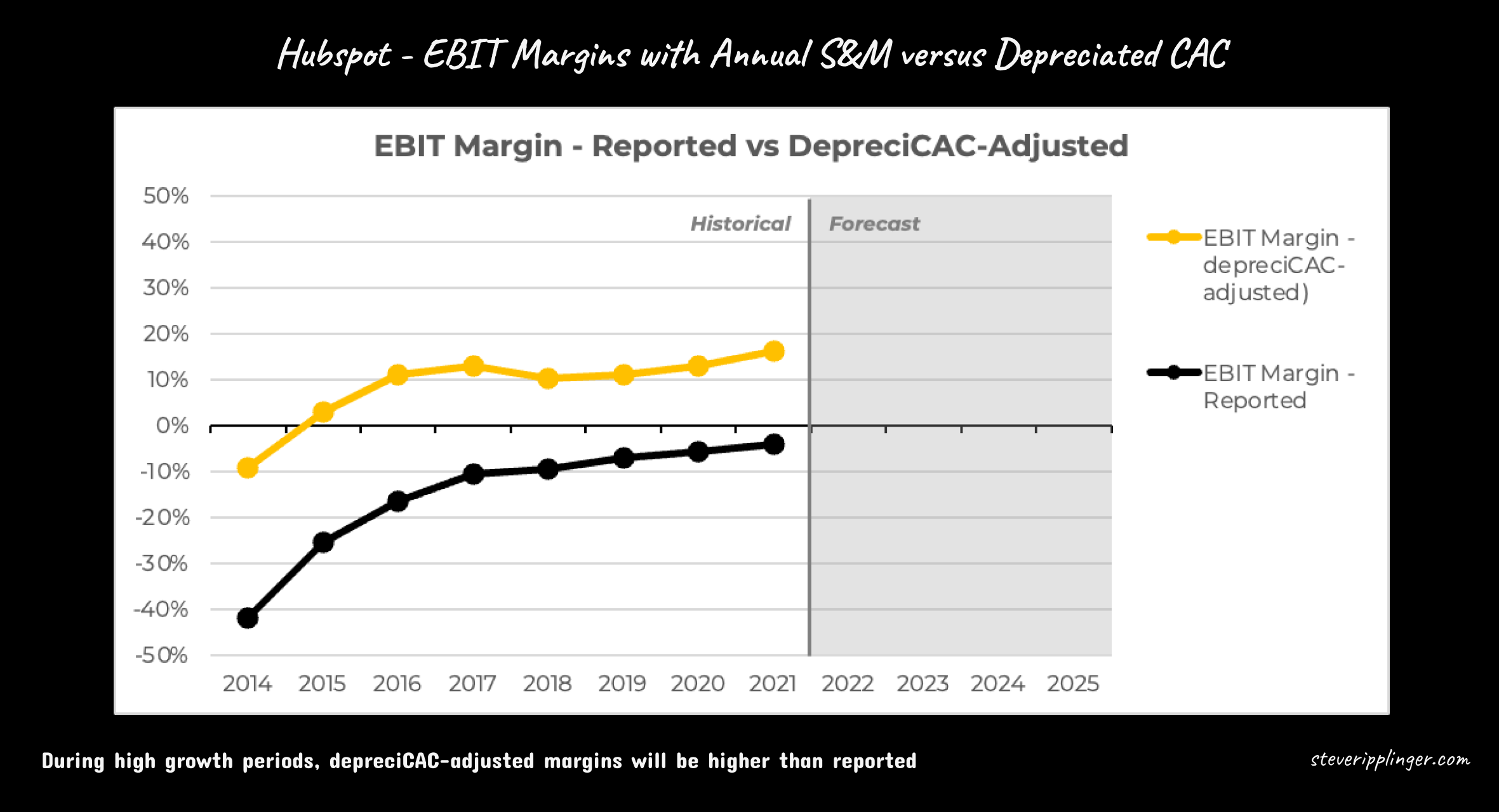

Since Hubspot is growing rapidly and spending more and more on S&M, the result is significantly higher profitability. Instead of $650M of S&M expense in 2021, depreciCAC is only $385M.

This drastically changes one’s view of Hubspot’s profitability. Instead of -4.2% EBIT margin, the adjusted margin is positive 16.2%. Valuation multiples beyond revenue now become applicable for Hubspot and similar companies, unlocking numerous interesting metrics and routes of analysis.

For any growing company, depreciCAC will be less than S&M expense. Over time, as growth slows, the effect weakens and these two methods converge. But, for companies that are growing fast, the difference is significant. In Hubspot’s case, it is the difference between negative operating income and positive operating income; a profitable business versus one that seemingly loses money every year.

This, of course, has potential for abuse and/or can be misleading, since anyone can apply this to any company and say it is more profitable than its reported income statement. Capitalizing S&M is not appropriate if S&M can’t reasonably be considered CAC, or if customer lifetimes are shorter than the depreciation schedule utilized.

But, to the extent S&M is being spent on new customer acquisition, moving CAC off the income statement is the entire point! CAC is a capital expenditure to acquire new customers for future revenue and thus shouldn’t overly penalize the income statement today. Whether or not the capital expenditure is economic is a separate matter that needs to be evaluated, just like any other use of free cash flow.

Which is an interesting point. In an assetCAC world, S&M (CACex) is a use of free cash flow, not an expense that reduces FCF. It is a discretionary investment and a capital allocation decision, as opposed to just being a part of the operating budget. Investing in CACex is a lever on how fast to grow customers, and just like an other capital investment decision, there are economics to consider whether makes sense to do so.

Another benefit to this approach is that the balance sheet better reflects the revenue-generating asset of the business - its customers. AssetCAC isn’t the full economic value since CAC is presumedly less than LTV, but putting all that CAC on the balance sheet as an asset is a step closer to the economic reality of the business. For Hubspot, there would be an additional ~$1B of value on its balance sheet in 2021.

Lastly, for full marks on the interview question, it is worthwhile to note that we should also adjust for taxes on the increased profitability, which I didn’t do in the above charts for simplicity.

Conclusions

Ultimately the goal is to better understand and manage SaaS and other customer-centric businesses. While great customer analytics frameworks (LTV, IRR, payback, cohort analysis, etc.) and valuation methodologies (CBCV) exist, there is effectively no link from customer economics to financial statements. S&M as capex bridges this gap, and is a complement to other customer-centric thinking. The nice thing is it can be done as a simple adjustment to currently reported financial statements - just capitalize and depreciate S&M each period over a time horizon that is aligned with customer lifetimes.

Treating S&M as capex is a fundamental shift in how investors and managers can view SaaS and other customer-centric businesses. It goes a long way towards reflecting the underlying customer-based fundamentals on the financial statements, allowing for better alignment of revenue and costs, a more accurate measure of profitability, more insightful analysis, and more predictability.

-

Some R&D can be capitalized, which can make sense in certain cases. Some “software development costs” can also be capitalized. ↩

-

Subscription here means any pricing model where there is a direct, account-based service - monthly, per seat, usage-based, etc. ↩

-

Unfortunately, usually only one-time at IPO and even then often with no y-axis 🙄 or excluding older cohorts. ↩

-

I’m not *actually* advocating for GAAP or IFRS rules to change. Better and more standard customer cohort disclosure would be more productive than forcing S&M to be capex at the reporting and tax level. But, for managers and investors, this is a useful framework for analysis and a mindset that has numerous benefits. ↩

-

Ideally you can delineate S&M that is CAC versus non-CAC (e.g. to retain existing customers), but in practice that is complex to do, and likely impossible for analysis of a public company. Assuming all of S&M is CAC is a valid assumption that works because is balanced out by no S&M expense post-acquisition, as long as it is consistent. Just note this assumption may overstate CAC (as well as PAV on the other side), especially in later years as an increasing portion of a company’s marketing spend becomes attributable to its growing base of existing customers, rather than new customer acquisition. ↩

Disclaimer: This post is strictly for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell any security. The views expressed herein are the author's alone and do not represent views of any organization or employer the author is currently or was previously associated with. Click here for full disclaimer.