The Habit Flywheel

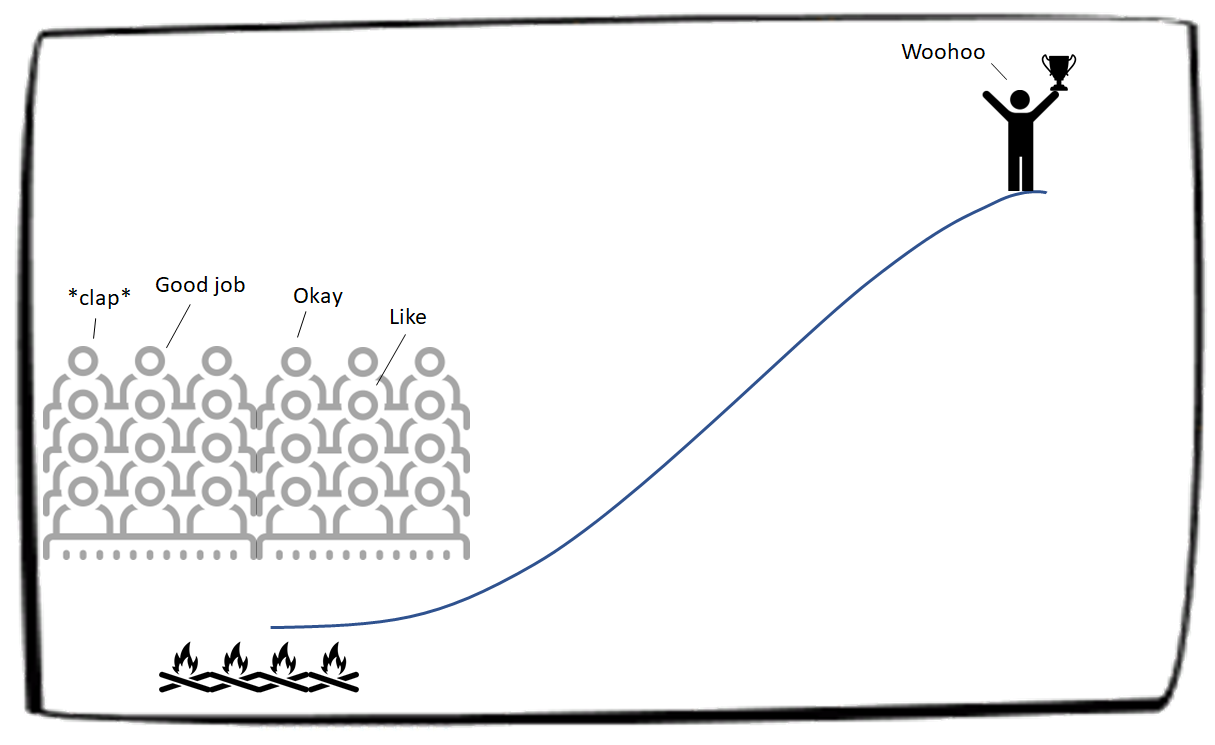

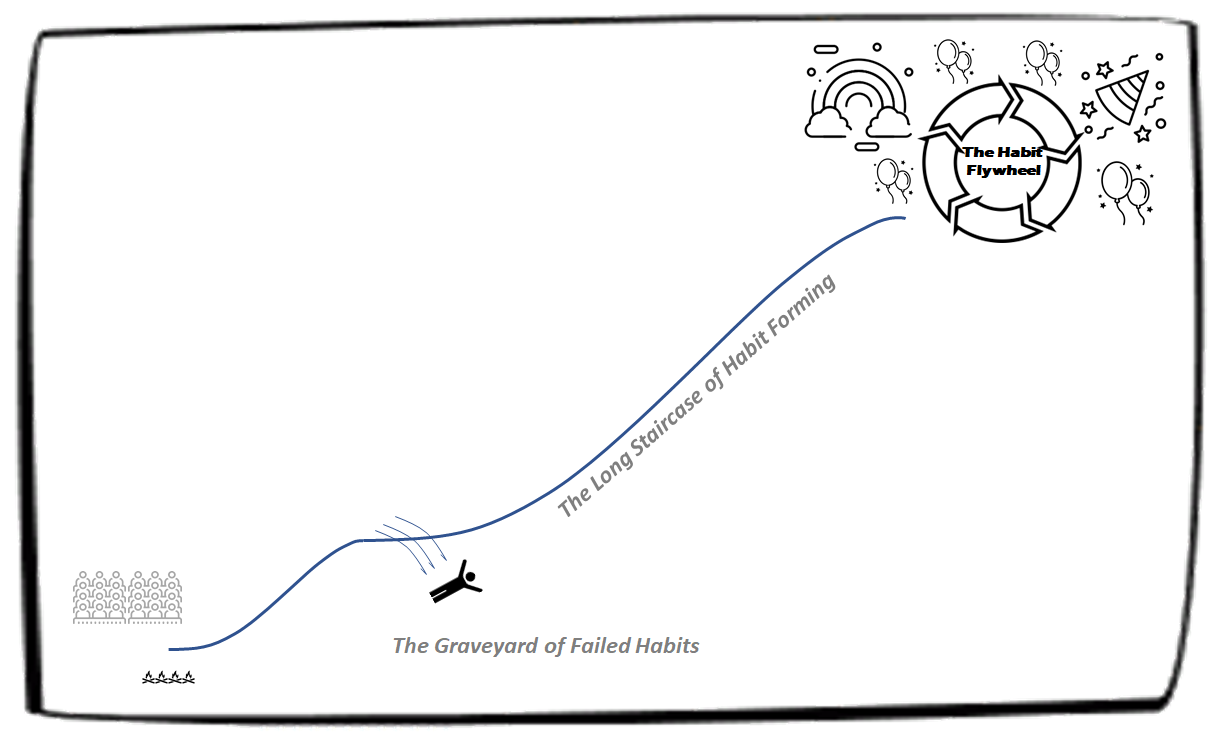

Starting a new habit can often look like this:

It can be hard just to do something once, let alone make it into a habit. But by understanding how habits work, we can take actionable steps to build better habits and stop bad ones.

A few months ago, I woke up one morning to the nudge and groan of my wife, who was startled awake by my phone’s alarm going off ten seconds earlier. She didn’t seem to like being an intermediary between me and my alarm clock, a human-device relationship made difficult by my use of ear plugs when sleeping. Her nudge was more of a shove, her groan more of a growl.

It was 9AM, a break from my recent destructive routine of getting up late, lounging in bed for an hour, and then getting up around 11AM.

This morning was different. I decided the night before that I was going to start running in the mornings.

15 minutes later, I was racing along the path by the river, the hot morning sun starting to coax drops of sweat from my back. The cobwebs in my brain started to disintegrate. Fairly quickly, I was amazed at my clarity of thought and ease at which ideas flew into my mind.

Problems I had been working through for weeks seemed to resolve. New topics to write about (including this one) became clear.

The value generated in such a short period was incredible. And the rest of the day? I was highly productive. Starting out a day having accomplished something seemingly makes the day an automatic success.

The next morning, I went for another run and experienced similar rewards. I told myself I should do this every morning.

And yet…

Within a week I was no longer running in the mornings. Too tired. Body needs rest. It’s raining. I’ll work out later in the day. Excuses galore.

Why is it so hard to form a new habit, especially something such as working out? And how can we make this easier?

Contents

The Habit Flywheel

Some people have great workout habits. We all know those people who run (and talk incessantly about) marathons, and others who show up to work in bike shorts that are a bit too aeronautically optimized.

Looking past the ostentatious virtue signaling, there tends to be an admirable consistency in some people’s workout habits.

Consistency is the part I’m interested in. A habit isn’t a habit without the habitual part.

Most likely, these spandex-laden humans have learned and felt the benefit of a habit such as running or cycling, so they keep doing it. The habit is fueled by the flywheel effect, and it is not something that needs to be jump-started every day.

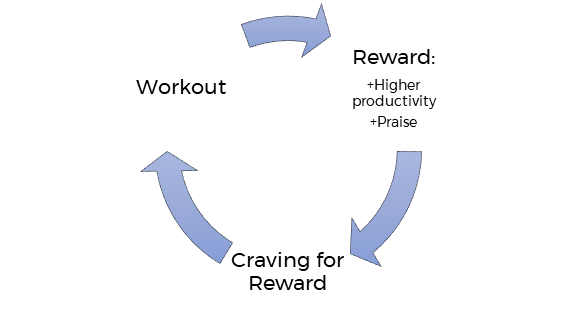

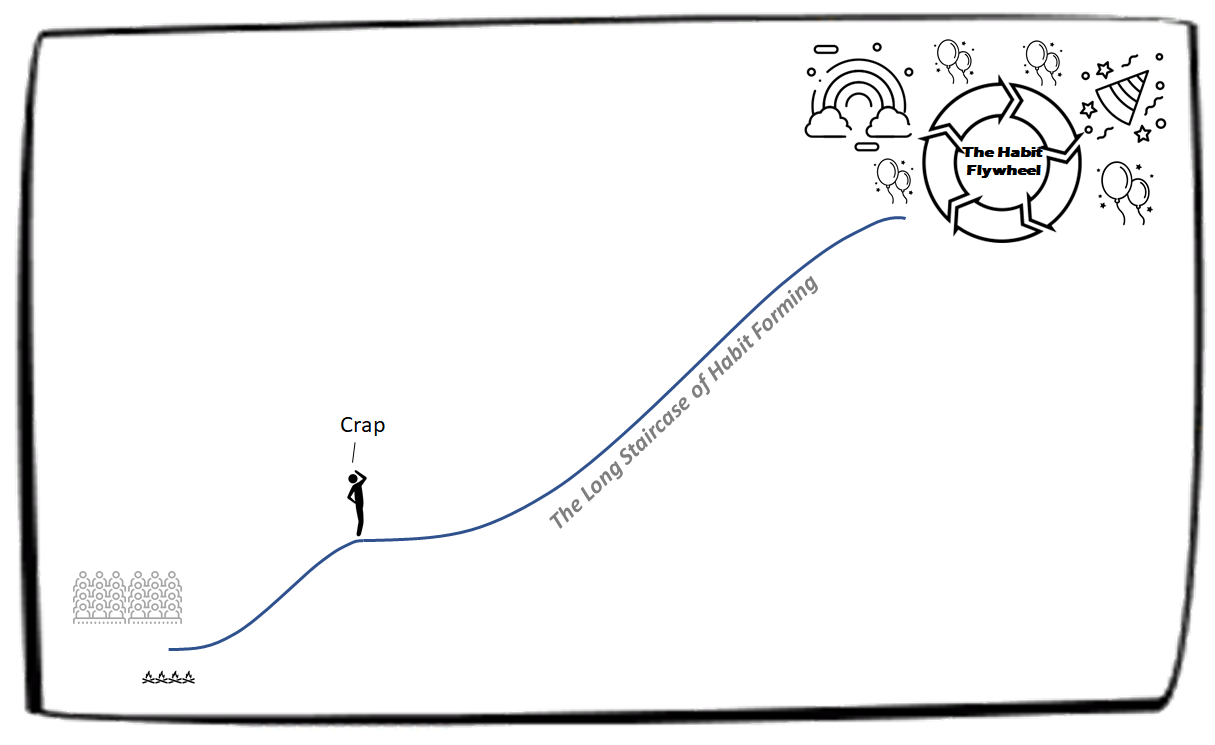

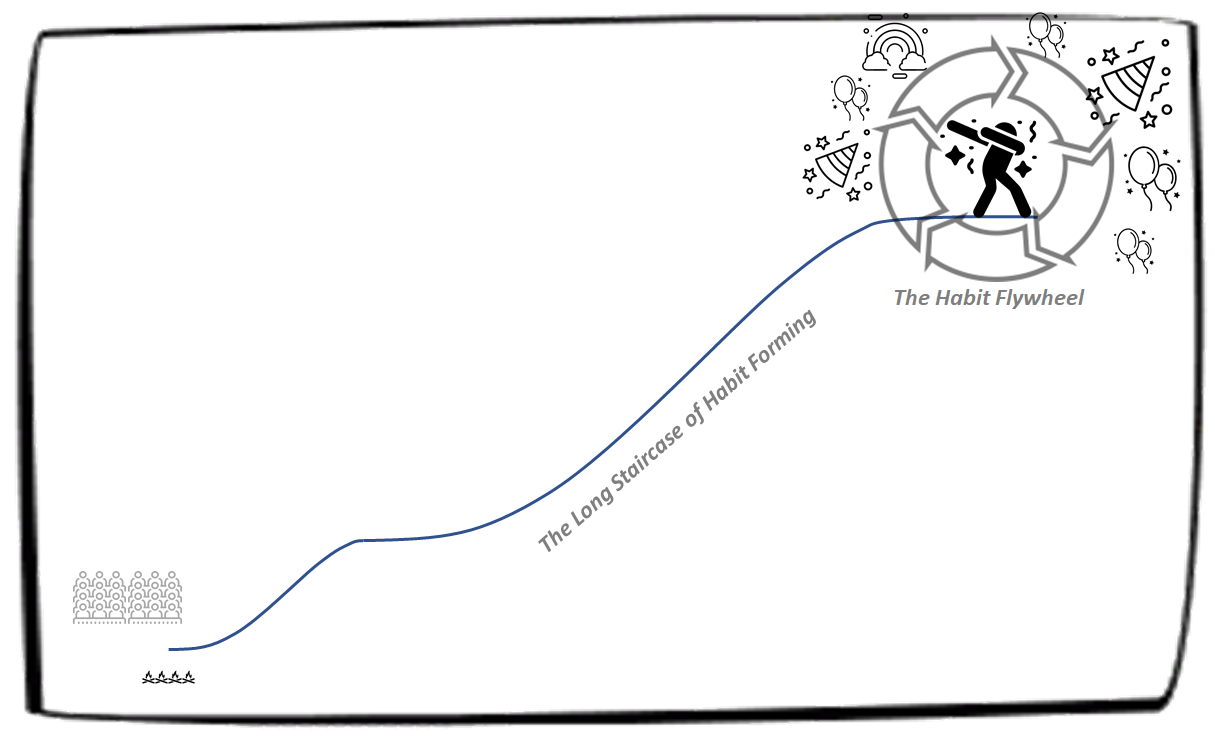

Sticking with the workout example, the flywheel might look something like this:

But the flywheel is step 3. It only manifests after the habit is formed and it is missing an important element. We’ll come back to this later.

Steps 1 and 2 come first. And they sure aren’t easy:

Step 1) Getting a Habit Started

“The secret of getting ahead is getting started.” – Mark Twain

For some people, self-motivation is enough to get started. It may be brought on by a catalyst (health scare, kids, a comment someone made) or it can simply be a decision to do it.

For others, it is more difficult. There is a chasm between desire and execution that needs to be bridged to hardwire the craving into our brains.

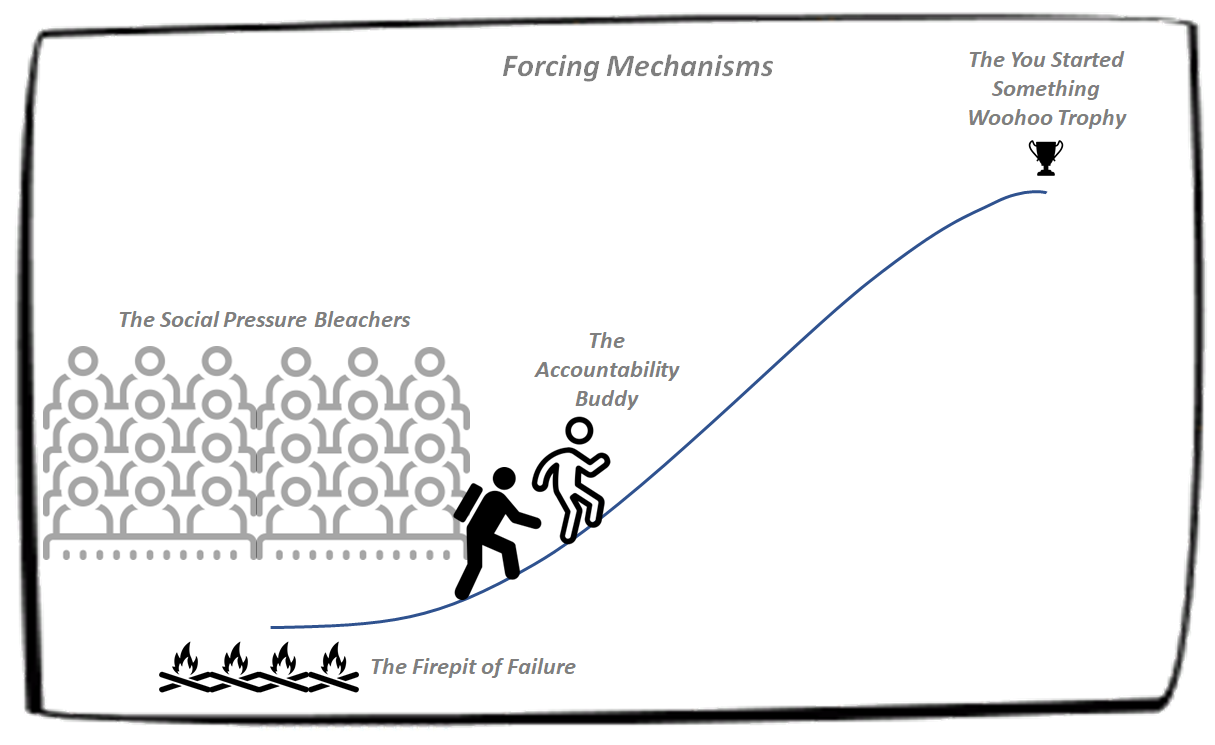

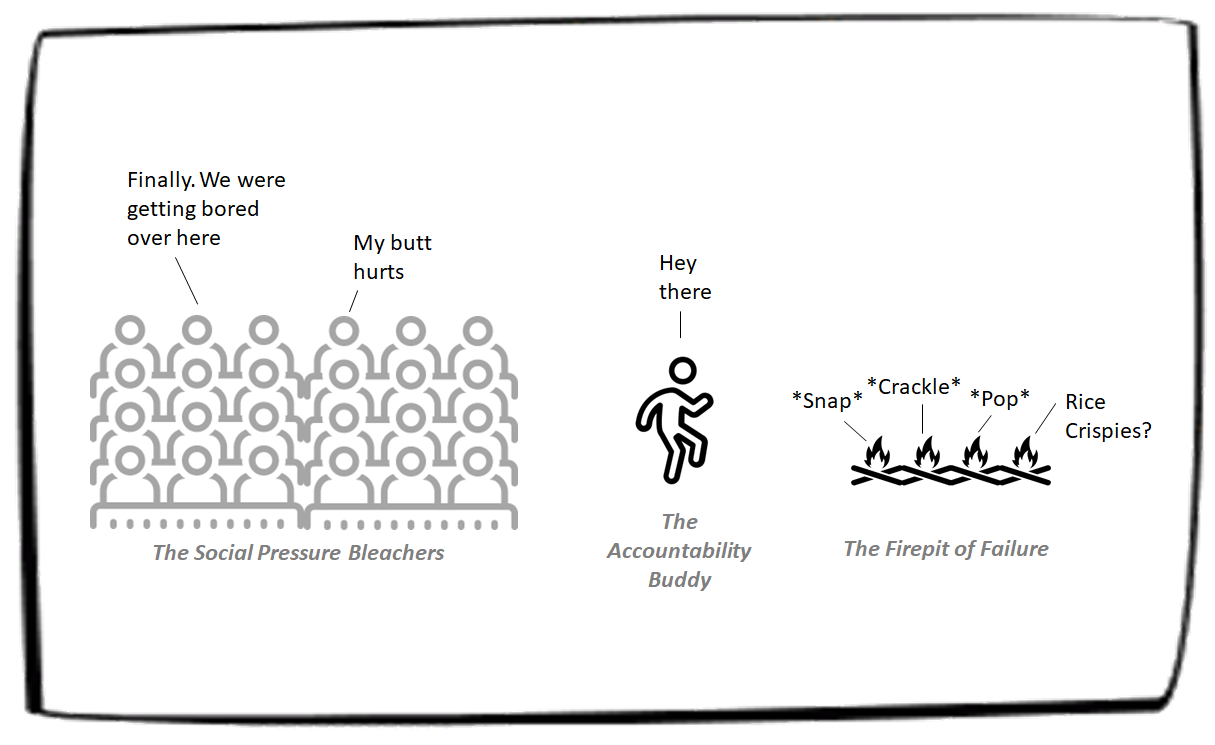

Forcing Mechanisms

This is where forcing mechanisms can help: something that increases the motivation component, primarily through social pressure and/or penalties for failure.

Social pressure spurs accountability. There is plenty of research showing that making your goals public increases the likelihood you will achieve them. Humans want to appear consistent and do not want to disappoint others.

If you don’t tell anyone else you will do something, you probably aren’t too serious about it.

But start telling your family and friends, and post on social media? Now you are seriously on the hook to follow through.

Public goals can be taken a step further: making a specific “accountability appointment” with someone increases your chance of success beyond just telling people. An offshoot of this is having someone do the habit along with you, which increases accountability through social pressure and competition.

Penalties for failure is one of the more interesting forcing mechanisms. A common early example is the proverbial “swear jar”, but technology has allowed for more extreme versions. For example, stickK is a commitment website/app that allows you to input goals and stake money on achieving them. My favorite feature is the ability to choose a cause you hate, an “anti-charity’, where your money will go if you fail to meet your goal, such an extremist political party, the NRA, or the New York Yankees Fan Club.

Any or all of these forcing mechanisms can work to get started on a habit. Even so, some degree of base motivation is needed or else you won’t even be willing to set up these mechanisms.

Whether getting started by sheer force of will or by use of a forcing mechanism, it is possible to start a new habit, like how I woke up in the morning a few times to run.

Unfortunately, getting started is just step 1. The flywheel is a long way off.

Step 2) Form Habit

The bad news is that habit formation is difficult and takes time to stick.

But the good news is that once habits are formed, they are hard to break. Just think of all the bad habits people can’t stop, such as smoking, biting nails, drinking, or unhealthy snacking.

To understand how to reach the habit flywheel, we first need to break down what makes something a habit.

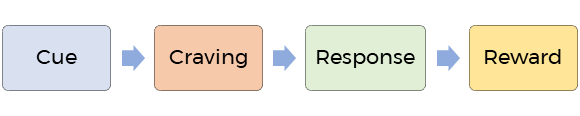

James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, has a great framework for how habits work in our minds:

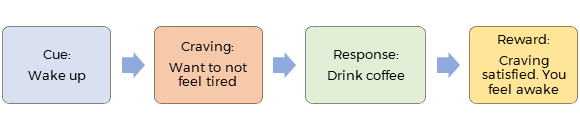

For example, many people drink a cup of coffee as soon as they wake up, which is comprised of these four parts:

1) Cue

Our brains are constantly scanning the environment looking for signs, or cues, of reward. At the most basic level, rewards are basic needs such as food, water, warmth, and shelter. Rewards can also be a wide range of human desires such as pride, joy, status, self-worth, approval, inclusion, money, or power. Anything that signals the brain that reward is possible can be a cue: waking up, a certain time of day, your phone vibrating, a feeling such as pain or stress, an action of someone else, or anything in your environment.

One reason coffee habits are so strong is because the cue of waking up is so consistent and observable.

2) Craving

Because cues signal that reward is possible or nearby, they trigger cravings for the reward. These cravings are the motivation for a behavioral response. Without cravings, there is no impulse to perform the actual habit.

Importantly, the craving isn’t for the response itself, but rather the change of your internal state. James Clear explains:

What you crave is not the habit itself but the change in state it delivers. You do not crave smoking a cigarette, you crave the feeling of relief it provides. You are not motivated by brushing your teeth but rather by the feeling of a clean mouth. You do not want to turn on the television, you want to be entertained. Every craving is linked to a desire to change your internal state. […] Cues are meaningless until they are interpreted. The thoughts, feelings, and emotions of the observer are what transform a cue into a craving.

My internal state after waking up is not a pleasant one, hence a strong craving to be less groggy.

3) Response

Next is the response – the actual habit. Executing the response depends on two things: 1) the strength of the craving; and 2) the ability and ease of performing the response.

The craving needs to be intense enough for you to perform the habit. At the same time, if doing the response is too difficult or there is too much friction involved, you won’t do it.

Drinking coffee in the morning is easy. Running? A lot harder.

4) Reward

Lastly, by performing the response, you satisfy your craving and claim your reward. Rewards satisfy our cravings and provide the benefit that our stomach is full, our thirst quenched, our needs met, our desires fulfilled.

More importantly, rewards teach our brains to recognize patterns and be on constant lookout for cues that lead to rewards.

When the Response Becomes Automatic

While all four steps of a habit always remain present, our brains love efficiency and thus create patterns and associations. Thus, drinking coffee becomes associated with waking up. We don’t even have to think about the craving and reward component. The habit simply looks like:

As the association between cue and response strengthens, the craving and reward melt into the subconscious and it is less critical to consciously recognize the craving. After enough time, drinking coffee in the mornings is automatic. You even plan your coffee ahead of time before you have the craving.

As the habit forms, any conscious struggle over what to do about the craving fades and the response becomes automatic,

A More Complete Flywheel

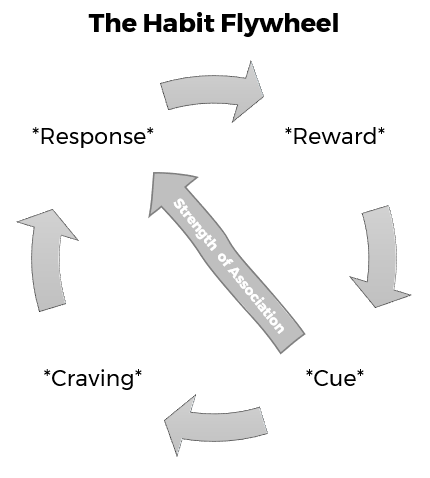

With this in mind, let’s update the Habit Flywheel to incorporate the cue component, as well as the concept of strength of association between cue and response.

Habit Formation

If all four of these elements – cue, craving, response, reward – are strong enough, and the cycle is completed enough times, it becomes a habit. A strong habit will have a strong association between cue and response.

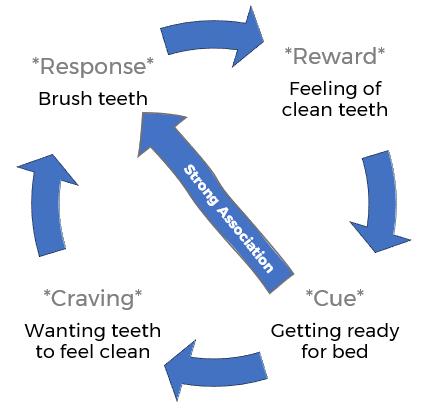

We can illustrate the strength of a habit by the vibrancy of the arrows in the flywheel. For example, brushing teeth before bed is a strong habit for me with all components firing on all cylinders.

Put simply, this habit is so strong because it all components of the flywheel are working with minimal friction and there is a fast feedback loop to reinforce the cycle.

Generalizing what makes a strong habit:

- The cue is strong and predictable

- The craving is intense and the connection to the cue is strong

- The response is relatively easy and frictionless

- The reward is immediate and satisfying

- There is high frequency and repetition to increase the association between cue and response.

Therefore, to form a habit, work on making these characteristics stronger. Similarly, to break a habit, weaken one or more of these elements.

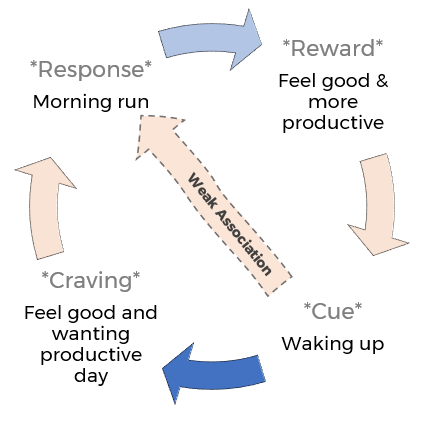

Going back to my aspirational habit of running every morning, this is how that looks:

Hmm. We can see now why forming this habit is difficult:

1) Transforming my craving into the desired response has A LOT of friction:

- I need to leave a warm bed

- I need my body to not be sore or injured

- I need a lot of energy

- I need to get dressed

- I need to get outside

- The weather needs to be decent

- I need to start running

2) The reward also isn’t perfect. I feel great during the run. And I might feel good and accomplished right afterwards. But my stated craving was also to feel good and productive for the entire day. The rest of my day is influenced by other things such that the reward and feedback isn’t immediate.

3) Lack of frequency. Repetition is what drives the strength of association between cue and response, yet I have only executed the response a few times. Meanwhile, I have woken up over 12,000 times in my life. My response-to-cue ratio is 0.02%. And even when I just started morning runs, I was only doing it two out of three days as sometimes my body needed a day off from running.

Since that first morning run of mine and now, it is no wonder I have failed in making this a habit.

Hacking your way to the Habit Flywheel

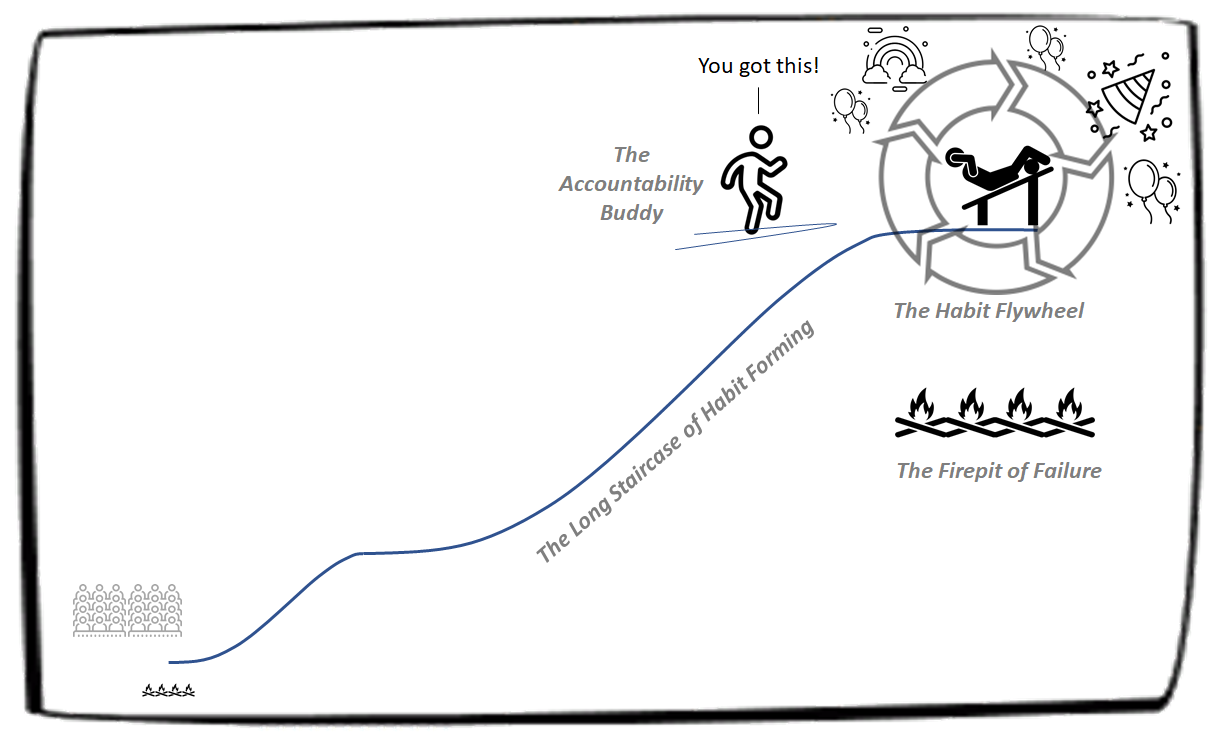

Now that we have a framework for habits, let’s break down how to climb the Long Staircase of Habit Forming and get the Habit Flywheel spinning.

Thankfully, forcing mechanisms are not just for starting something – they can also be used on a long-term basis. Now that we have a framework, we can be more precise on how exactly to best use these tactics.

The key is to make sure all elements of the Habit Flywheel are doing their part. Here are some ways to boost each element and form a strong habit:

1) Make it realistic

After realizing how unrealistic my running goal was, I changed my desired habit to any type of workout. It was unrealistic to run every day while also playing hockey, lifting weights, or doing any of the other activities I enjoy.

I also realized that not only is running every morning unrealistic, so is working out every single day. There are days when I’m traveling, too busy, or my body just needs to recover. Instead, my new workout habit goal is to never have two consecutive days of not working out.

This modified goal has been incredibly effective because it takes a lot of pressure on days when there is a lot of friction to getting a workout in. It also flips the default to working out, which is a better way of framing things.

2) Make it measurable

The first step in trying to improve anything is to make it measurable. Wearing an Apple Watch is the single biggest contributor to making working out a sustainable habit for me. I simply put my watch on as soon as I wake up – an easy habit in itself to form with an obvious cue and very little friction to the action.

Depending on the habit, the measurement process might be different - it can be as simple as recording what happens in a journal or spreadsheet. However, make sure that the recording/measurement process itself doesn’t become a challenging habit.

The other important element is to identify Key Performance Indicators. For working out, it is easy as Apple Watch has activity indicators including calories burned, workout minutes, and stand hours. Closing those rings is a powerful motivator.

3) Change the cue, or at least something about it

If your desired cue is something you’ve done ten thousand times in your life, it can be difficult to suddenly add a habit on top. That’s why it is much easier to start a new habit at the same time as another major change in your life such as moving to a new home or new city.

Recently, I moved to a new city and used this major life event as an opportunity to make working out a more enduring habit. My cue-to-response ratio of waking up in not-my-new-city to running was 0.02%. My new cue-to-response ratio of waking up in my new city to working out: 80%.

4) Use a craving substitute

This is where forcing mechanisms can really help. Rather than focusing on a craving such as feeling good, tap into your deeper and more powerful desires such the need to win, social pressure, or fear of failure.

Instead of working out to be more productive, which is my actual goal, I get more immediate and intense satisfaction closing my Apple rings every day. Apple also has a feature where you can compete on activity with your friends. This is also very motivating – I hate to lose any kind of competition.

I also made my goals public, letting my wife and others know that I am someone who works out almost every day. The social pressure helps and taps into my fear of failing in front of others.

5) Simplify the response

Another helpful change was to reduce friction of the response. My workouts do not need to be an hour long, require a gym, or burn X number of calories. They often are intense, but if time is a constraint or if I’m not really feeling it, simply doing pushups and ab stuff for 20 minutes is enough.

Step 3) The Habit Flywheel

For some habits, the dynamics might be so strong that the flywheel does all the work once it is formed.

But for most other habits, the flywheel will be more wheel and less fly. The dynamics behind the habit might stay more conscious and need to be maintained. Our forcing mechanism friends may be necessary to keep around.

For me, the habit of working out is in the latter category: it requires ongoing effort.

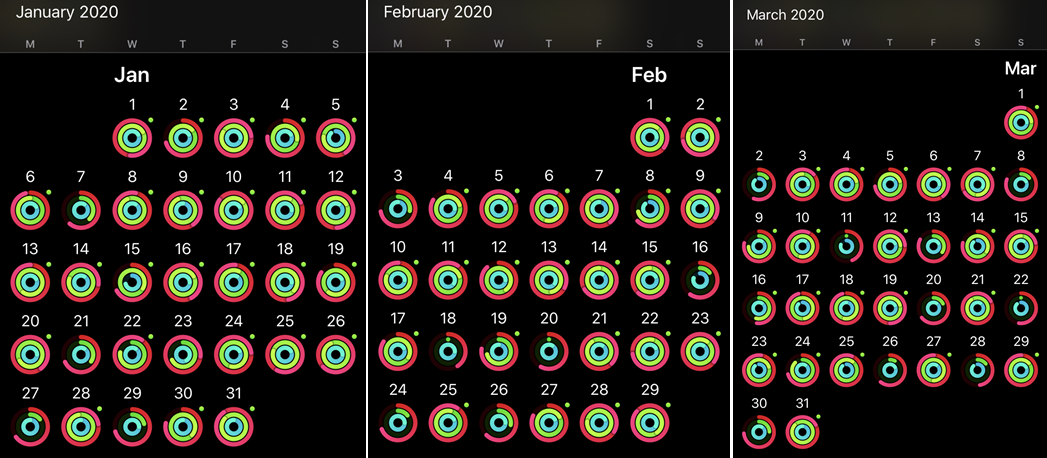

But it gets much easier over time. For all of 2020 thus far, I have achieved my goal with no two consecutive days of not working out:

And hopefully by posting this, it is another forcing mechanism to keep this habit flywheel going.