Musings #9

Innovation & Moonshots

It is rare for companies to have “second acts”. Most companies have a hard time organically expanding beyond their initial product area:

Today such enterprises are few and far between. Most are found in the pressure cooker of the internet ecosystem, where survival instincts are of necessity the most valuable entrepreneurial trait. But for every successful second-act enterprise, a hundred once-promising disrupters simply disappear. - Finding Your Company’s Second Act (HBR)

For an investor to have an intensity delta over the long term, it is necessary to have some imagination about a company’s future beyond it doing the same thing it is doing now. Extrapolating current growth rates is first-level thinking and a commodity. Everyone can do that.

Which is why one thing I like to follow is what else tech companies working on. For example, it is well known that Alphabet has a Moonshot factory called X, which is where Waymo and Glass came from. Similarly, Amazon has Lab 126, which is credited for creating the Kindle and Echo. But what are these future factories working on now that could become significant products or business lines in 2-10 years?

Many of these projects being worked on are secret, though some aren’t - they just aren’t that well covered and/or are heavily discounted because they aren’t launched yet. And that makes sense as “moonshot” projects are high reward but also very much unlikely to be successful. By definition, they are breakthrough technologies, which are not only difficult, but also don’t happen too often.

To that point, it is worth not getting too excited about most of these projects or pricing them too much into a company’s stock. Indeed, just consider some projects X has worked on. From Wikipedia:

Projects that X has considered and rejected include a space elevator, which was deemed to be currently infeasible; a hoverboard, which was determined to be too costly relative to the societal benefits; a user-safe jetpack, which was thought to be too loud and energy-wasting; and teleportation, which was found to violate the laws of physics.

Bummer about that last one - I would love to teleport instead of fly on airplanes. But that said, these projects are worth following because they could turn into something and because identifying inflection points in technologies, companies, and sectors is an opportunity for incredible value creation.

To avoid getting hopes up on the really far out ideas, it can be more useful to look at when these projects stop being moonshots and start to have more potential to be commercial products in the next couple years.

How can one identify these inflection points? For some, the companies actually talk about them. For others, the press sometimes mentions them. Acquisitions can also be very telling. Another great source: patent filings and job postings. It is reasonable to conclude that if a company is ramping up hiring for the specific project and receiving a significant number of patents in that area, it has a good shot at launching and potentially at being meaningful.

After all that pre-amble, it would be empty to not give a few examples. Apple has a couple “moonshot” projects that are near inflection points of becoming reality including AR glasses and self-driving cars. NVIDIA is working on its Omniverse. And a handful of other companies including Google and Microsoft are making incredible advances on AI, large language models, and other game-changing areas such as text-to-image that we are just scratching the surface of.

prompt: ‘a hockey player on the moon photorealistic’ on craiyon

Will leave it there for now but will likely revisit this topic over time.

Seeing the Present

Speaking of innovation, it is remarkable how few people are aware of current technologies and innovations, let alone future ones.

A good example is GPT-3 and the large language models mentioned above. This recent anecdote from Edward Nevraumont (who writes the great MarketingBS newsletter) is shocking:

I was at an event for CMOs of Warburg’s portfolio companies a few weeks ago. The CMOs were all very successful people overseeing massive, rapidly growing technology companies. In every casual conversation I had, I asked how they were thinking about GPT-3 and NLP models. Not a single CMO had even heard of GPT-3, let alone thought about how to apply the capabilities to their businesses. Maybe that will change now that the topic made the cover of The Economist. But if so, it will only move the needle a tiny amount. Most people are focused on blocking and tackling and have no capacity to think about non-traditional ideas and technologies

Lack of capacity may be a part of it, but a key point is that this isn’t even about predicting the future, it is about not even “seeing the present” (a good line most oft attributed to Matt Cohler from Benchmark) as this technology is already here.

This is also a good reminder of curse of knowledge - the cognitive bias of overestimating how much other people know about things you know. If I spend most of my time on technology and it is a large component of my information diet, it is easy to be surprised when someone doesn’t know something that seems obvious to me. Though that may just be because that person cares more about other things - and they may think the exact same thing about me for things I don’t spend time on.

Regardless, this goes to show that simply “seeing the present” can be a powerful competitive edge on its own.

Substack’s New Reader

Substack released a reader app a couple months ago, which is similar to its web version. Ben Thompson has a good analysis (paywall) of the strategy that is worth a read. Similar to his framework, I have a few different lenses to view this: as a strategist, as a reader, and as a writer that uses Substack.

As a strategist, it makes a lot of sense for Substack to be an aggregator and control the user-facing experience. This does three things. First, as an aggregator, it consolidates the experience into something it owns, which facilitates value capture (primarily bundling but could include advertising or other opportunities). Second, it allows Substack to own the entire value chain from writers to readers - why let gmail own and mess up the last mile of the reading experience (promotions folder, truncated emails, etc.)? And lastly, it helps solidify the Substack as more than a ”faceless publisher”, as Ben aptly puts it.

As a reader, I also like the new reader app. I have over 70 Substack subscriptions 🤯, although many are inactive or infrequent, and quite a few I only read if the topic is especially interesting. However, as a reader I like to take notes and need to sync it to my knowledge management system, and Substack lacks this key feature. For a reading app that can save highlights, Matter still wins, although I’m looking forward to trying Readwise’s app when it launches.

As a writer that uses Substack, I like it because if someone prefers a native reader app to read what I write, in the original intended format, then great. My posts are less likely to get lost in a reader than they would in someone’s busy inbox. That said, I say “as a writer that uses Substack” rather than the more common vernacular “as a writer on Substack” because this is self-publishing where Substack is a tool for email delivery (and a landing page). I chose to use Substack because it was the best available across various dimensions (design, free, etc), and only because it leaves ownership in the hands of the writer.

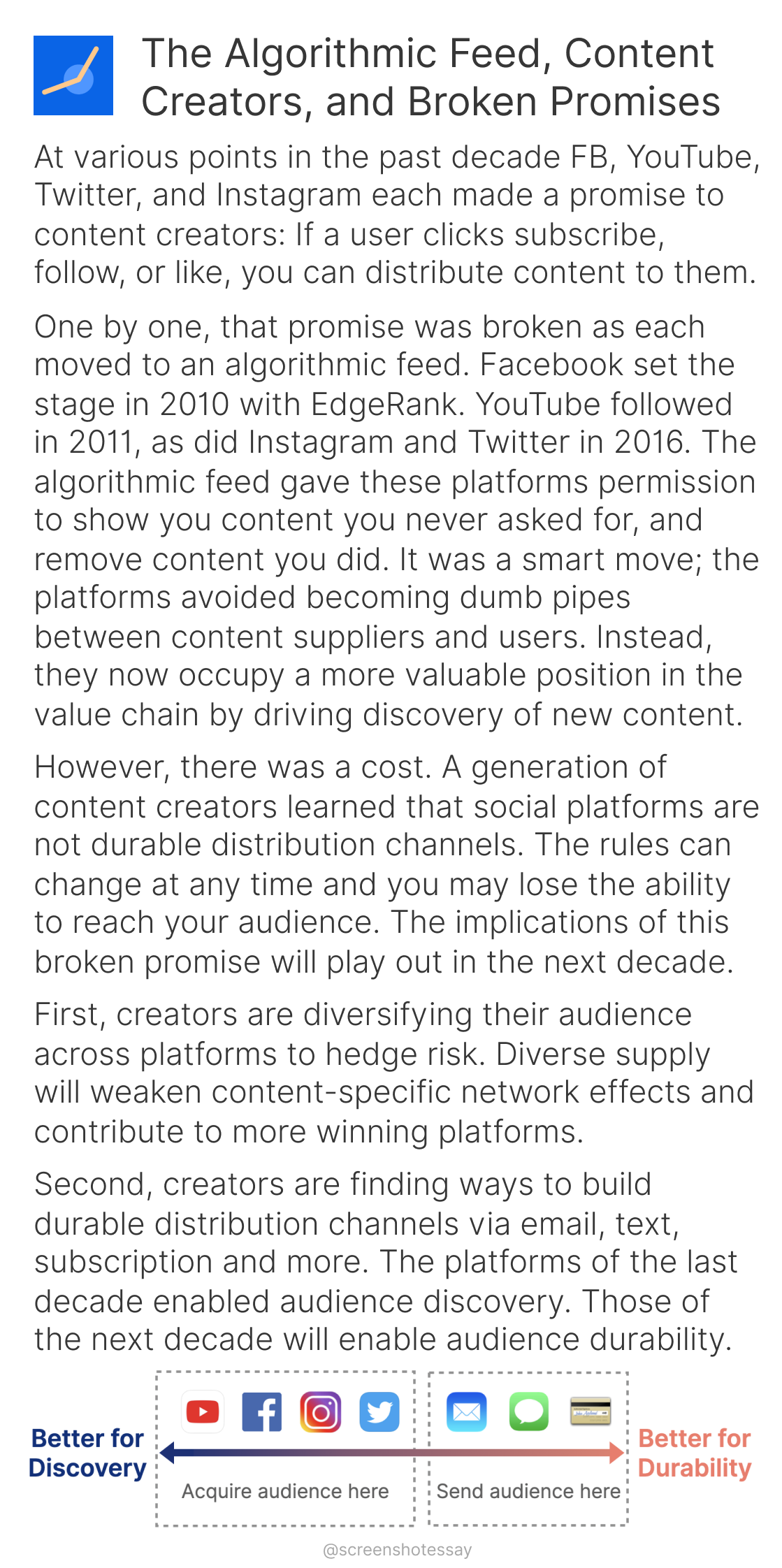

Lastly, Substack says in a writer FAQ that “there won’t be any confusing or complex algorithm getting in the way”, which I really hope it lives up to. I’m constantly reminded of this great screenshot essay on how the algorithmic feed destroys both the creator and the user experience:

Curveballs

-

”Mark Twain said kids provide the most interesting information, “for they tell all they know and then they stop.” Adults tend to lose this skill. Or they learn a new skill: how to dazzle with bullshit.” - Different Kinds of BS (Morgan Housel)

-

“One way out of this is to perhaps explicitly ask something along the lines of “what’s the most outrageous advice you can come up with? what advice are you scared of giving me because you think I’ll blame you if it fails?” - Every thought about giving and taking advice I’ve ever had, as concisely as possible (Alexey Guzey)

-

“They gathered two decades of data from 5,200 subjects, crunched the numbers, and discovered that the greatest indicator of life span wasn’t genetics, diet, or the amount of daily exercise, as many had suspected. It was lung capacity.” - Breath (James Nestor)