Musings #2

Third-Level Thinking

One of the lessons that has stuck with me over years is second-level thinking. From Howard Marks in The Most Important Thing:

First-level thinking says, “The outlook calls for low growth and rising inflation. Let’s dump our stock.” Second-level thinking says, “The outlook stinks, but everyone else is selling in panic. Buy!”

First-level thinkers think the same way other first level thinkers do about the same things, and they generally reach the same conclusions. By definition, this can’t be the route to superior results. All investors can’t beat the market since, collectively, they are the market.

This was always a reminder to me to always go one step deeper; to always ask the next question. In investing, you can do well if you can “anticipate the anticipation,” as a mentor of mine often said.

Third-level thinking takes that to another level. There was a fantastic example of this recently on a podcast featuring Nick Kokonas, the founder of Tock and numerous famous restaurants including Alinea, Next, and The Aviary.

In the restaurant business, first-level thinking is to take payment after diners eat at the restaurant. It’s what everyone does.

Second-level thinking is to have diners pay in advance. Part of that in this case is re-framing it as an experience, much like a show or event. There is no “reserve a table” button on Alinea’s website - it is “Book Your Experience”. From the podcast:

When we were building Next, I just decided this is a theater-like restaurant. It changes three times a year to an entirely new menu. I’m going to sell tickets to this. And again, everyone in my own company thought I was an idiot. So I had to hire an outside programmer, had to not get a phone on purpose. We barely built it in time and it broke right away because it was a home brew software. But then the first day we sold $562,000 in tickets to a restaurant for the first time ever.

This solves so many problems and creates many benefits. For example, you no longer have to worry about no-shows. You also know what each customer is going to do when the come in such that you know what to prepare in advance.

I especially like that the payment is decoupled from the experience, which makes it more enjoyable and feel more valuable - the cash outlay was so long ago it is only upside now. Imagine if you had to pay for a broadway show on your way out - if it was good, having to think about cost would be a downer, and if it was bad, you would be upset you have to pay for something that you didn’t enjoy. It’s a losing proposition either way.

Perhaps the biggest outcome of advance payment is the creation of positive working capital. If you can receive payment ahead of time, and before you have to pay your suppliers, that is a lot of cash on your balance sheet. That’s valuable.

Most people would stop there and think that’s great.

Here’s where third-level thinking comes in:

And when we started to bring in money through deposits and prepaid reservations, tickets, I suddenly looked and had a bank account that had a couple million dollars in it of forward money. Like a lot of other businesses. Like the computer business. If you buy a computer then they ship it to you five days later kind of thing. So you have a float. So I started calling up some of our big vendors for big expensive items. Proteins, meat, fish. Luxury items like caviar, foie gras, that sort of stuff. And wine and liquor. And just said, “I don’t want net 120 anymore. I want to prepay you for the next three months.” And they had never had that phone call from a restaurant before. So basic economic theory would say well, how much should they discount it?

Let’s say we’re going to buy steaks and they were $34 a pound wholesale for dry aged ribeye. We’re going to pay $34 a pound wholesale, get net 120. And I called the guy and said, “I’m going to use 400 pounds of your beef a week for the next four months for our menu, which is about $300,000 of beef. What do we got if I prepay you?” And he was like, “What do you mean?” I’m like, “I want to write you a check tomorrow for all of it for four months.” And he was like, “Well, no one’s ever said that.” So he called me the next day. He said, “$18 a pop.” Half. Half price.

Now, I know huge restaurant groups, huge restaurant groups that look at their float as more valuable to have that money in the bank and to pay their vendors net 90, net 120, whatever. What are you earning in interest these days? 1% a year or something like that? It makes no sense to do that. It makes sense to get ahead of that curve, estimate your next month’s sales, and prepay for the food.

In other situations where you need capital to grow, it may make sense to use the positive working capital for that. But in this situation, using your float to pre-pay suppliers is incredibly smart.

The interview with Nick is full of many other amazing insights.

Customers as the Economic Unit of Value

I’m obsessed with customer analytics. Specifically, the idea that customers should be the focal point of, well, everything. Generally, it is how management of a company should view its business and it is how investors should model and value a company. To paraphrase a professor of mine: customers are the rows on your spreadsheet, not products or business lines. In other words, profitability should be measured per customer instead of per product.

This customer-centric thinking is by far the most impactful concept that I took away from my time at Wharton, inspired especially by Prof. Peter Fader (who literally wrote the book on Customer Centricity), to the point where I spent months after graduation learning the intricacies of customer-based corporate valuation (developed by Dan McCarthy and Fader) and applying it to Chewy’s IPO.

This concept is starting to get more traction. Last week, Michael Mauboussin published an extremely well done overview of customer economics based on CBCV:

The report dissects CBCV and addresses CLV, cohort analysis, retention curves, and CAC. But it also intertwines many other marketing/finance concepts and frameworks such as variables for product diffusion, WTP and WTS for value creation, and customer churn predictors. Worth the read.

Hairy Charts

Talk of inflation is heating up these days:

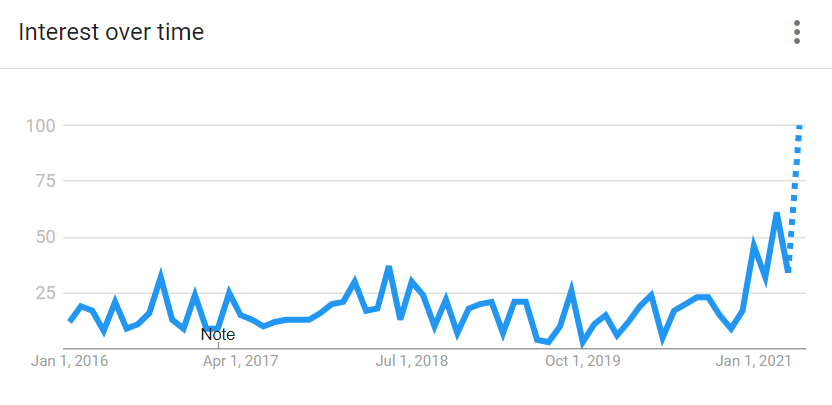

To better illustrate the inflating inflation discourse, here is the Google news trend result for “Inflation”:

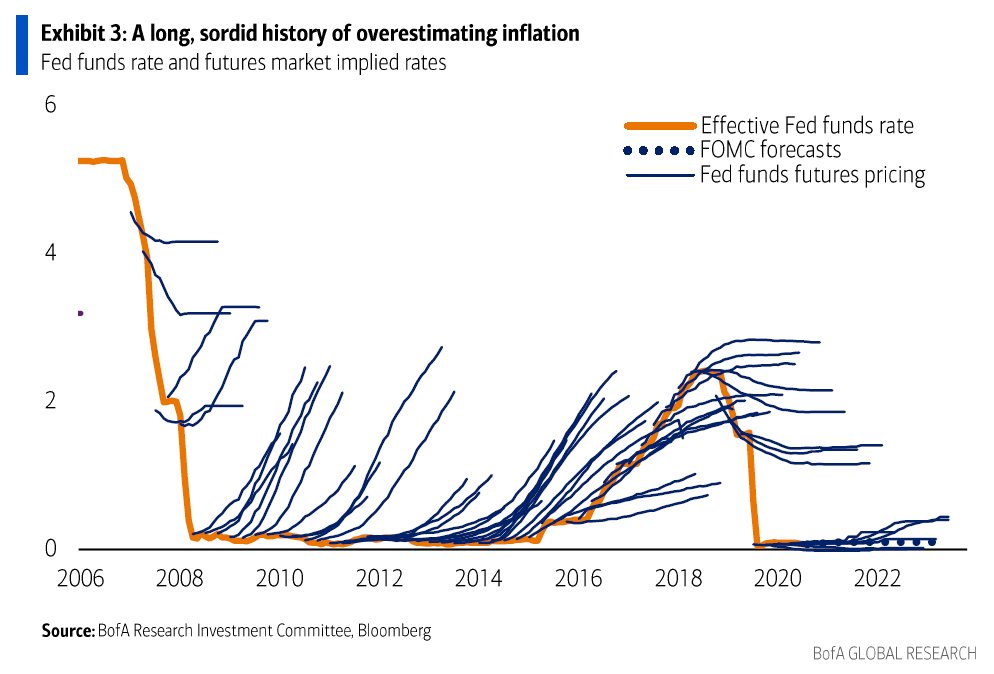

With zero comment on inflation today or what is going to happen, it is worth pointing out that forecasting macro events is very, very difficult. In that vein, one Bloomberg reporter tweeted out this “hairy” chart:

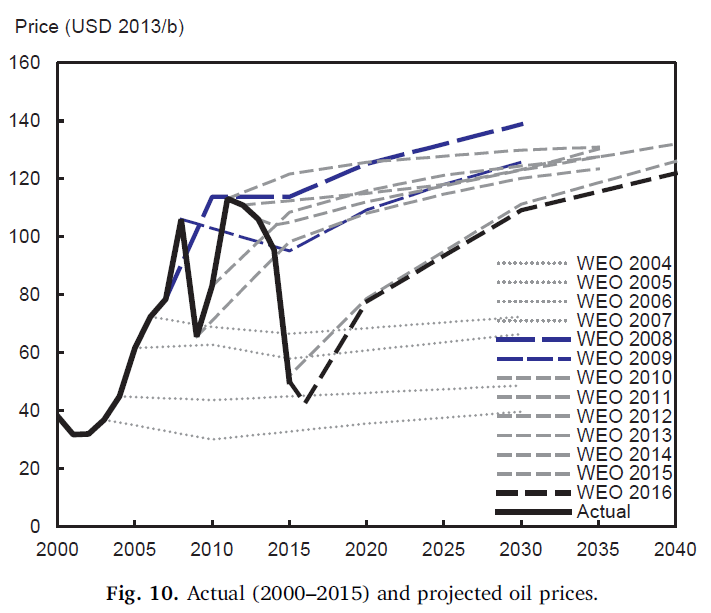

This reminds me similar charts for oil prices illustrating how the major energy agencies and think tanks would constantly get oil price forecasts laughingly wrong:

This isn’t to necessarily harp on these forecasters (although these are awful) - after all, forecasting is hard. And in any case, the quality of the forecast should be judged based on the decision-making process at the time, rather than just the outcome.

To that end, forecasts should always come with confidence levels or probabilities. Yet this is rarely the case in practice.

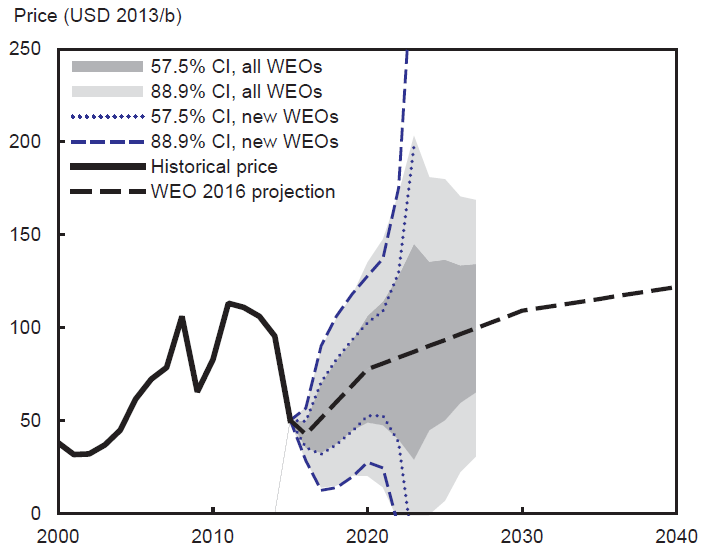

The above oil price chart comes from a study in which the authors dissect IEA’s oil market predictions and use the empirical results of prior forecasts to calculate uncertainty in IEA’s current (at the time) point forecasts. The punch line is that the confidence interval is so wide that these price forecasts are effectively worthless:

From a probabilistic view, taking the five year horizon as an example, this result implies that the WEO 2016 five year ahead point projection for year 2020 of 78 USD/b has at best a 58 percent chance of being within 49–107 USD/b, or a 89 percent chance of being within 20–135 USD/b.

Here’s what looks like in chart form from that study:

Actual oil price since 2016 has generally hovered in the $40-$70 range with a dip well below that in early 2020.

Speaking of expectations and paths…

Life Paths

Photo of the week

After a wonderful hike in a redwood forest, I came across these deer just grazing in a clearing. They looked so serene and peaceful, enjoying a meal before sunset.