Musings #3

On Interestingness

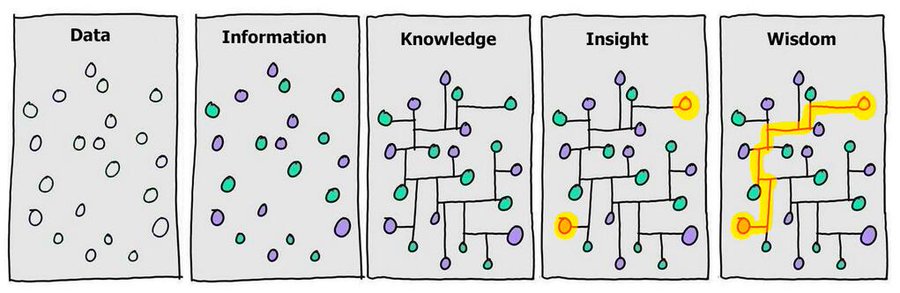

One of the best barometers of the interestingness and/or quality of an idea is how long it stays in your “active mind”. After hearing or reading something, when and how often do you think about it again? A great idea that truly broadens your perspective is one that you continue to actively think about and ponder for weeks, months, or even years.

For me, and I suspect most people, most of the information I consume goes into my brain and gets immediately filed into my “passive memory” - likely never to be thought of again unless something just happens to spark a connection. But passive memory is low fidelity, and unless regularly pinged, the information fades with time. This is a feature, not a bug; our brains are highly sophisticated machines that try to be efficient with information storage and retrieval, keeping only the things it deems important at the front of the filing cabinet.

Which is why when something sticks with you for more than a day or so, it is a very strong signal. One reason I write is to identify and “permanently” store those ideas that have been on my mind for the last while. Symbiotically, it is also a threshold for what makes it into this newsletter and explains my monthly-ish cadence - I want most of the musings here to be above the superficial; to be worth thinking at least a little bit more about (though I’m certainly not above including some fun tidbits or things purely for entertainment).

Taking this one step further, the ideas that stick in your active mind beyond a few months become knowledge; and clusters of knowledge translate into permanent lenses that you see the world through and a base level of understanding to apply to new data. And I find that by writing about these ideas, you solidify and greatly enhance this process.

A few of the broader themes from the past few years that have been added to my permanent active mind:

- Probabilistic thinking

- Consumer behavior as three distinct processes (acquisition, churn, and spend)

- Feedback loops and behavior change

- Luxury as social stratification

- Inflection points

- Status/social dynamics

- New ways to think about valuation (long-form post on this is in the works)

By the way, two other tests for idea quality: 1) if you start writing about it, how much depth is there? If new thoughts, applications, caveats, and dimensions keep flowing, you’re on to something; and 2) how pervasive is it across different domains? If you start being able to apply it to different domains and connect two disparate nodes, it is probably quite powerful.

Concentration Level Dependent on Market?

I thought this old quote from Bill Miller was interesting:

Concentration works when the market has what the academics call fat tails, or in more common parlance, big opportunities. If I am considering buying three $10 stocks, two of which I think are worth $15, and the third worth $50, then I will buy the one worth $50, since my expected return would be diminished by splitting the money among the three. But if I think all are worth $15, then I should buy all three, since my risk is then lowered by spreading it around.

A central tenant of my investing philosophy is a concentrated portfolio. This was true when I was managing a fund, and it is even more so now with my personal portfolio. The rationale is simple: my 5th best idea will always be better than my 30th and I think it is rare to have more than a handful of high conviction ideas. So my thinking is to always have a concentrated portfolio.

But the scenario in the quote is interesting: what if it is a time when it is hard to find those “fat-tail” ideas? The easy answer is to be more creative and do more work because there are always going to be stocks that do well, but let’s assume you’ve exhausted your universe or you don’t have time. I see three main possibilities:

- Diversify, as the quote suggests, by owning more companies at lower weights. The retail investor version would be to just own an ETF.

- Stay concentrated (and perhaps even more concentrated) in your few good ideas.

- Go to cash.

The answer to me is pretty clear: a combination of 2 and 3. I would own as much as I felt comfortable with in the companies I want to own for the long term, and hold cash until I find better opportunities. In a market scenario with low return expectations and few good ideas, the last thing I want to do is own lower conviction names that I probably don’t know as well, which likely means more risk, not less.

Silence is a Luxury Good

From the Lindy Newsletter:

Contrast the world of the airport and its commons — saturated in advertising, filled with mesmerizing screens, flashing lights — with the quiet, ad-free world of a business lounge: To engage in playful, inventive thinking, and possibly create wealth for oneself during those idle hours spent at an airport, requires silence. But other people’s minds, over in the peon lounge (or at the bus stop), can be treated as a resource — a standing reserve of purchasing power.

Silence and attention are a luxury good.

The pictures (same source) make this obvious:

You’re not paying to not see ads; rather, you’re paying for peace and quiet - for your eyes, ears, and brain to be free from bombardment-style advertising.

Personally, I do everything possible to not see ads (adblocker is a godsend), but consumer behavior is heterogeneous. There is a reason why people don’t pay the airport lounge fee and why 57% of Spotify MAUs are ad-supported. But in return for keeping more cash in your pocket, you’re paying for it with your attention and you are incurring opportunity cost of what your mind could otherwise be doing.

Curveballs

I capture highlights from all the things I read. A few noteworthy ones of late:

-

“In our survey of the scientists who received Fast Grants, 78% said that they would change their research program “a lot” if their existing funding could be spent in an unconstrained fashion. We find this number to be far too high: the current grant funding apparatus does not allow some of the best scientists in the world to pursue the research agendas that they themselves think are best.” - What We Learned Doing Fast Grants (Patrick Collison, Tyler Cowen, Patrick Hsu)

-

“None of the classic papers on DNA, nor Einstein’s four in his miracle year, were peer reviewed. Indeed, only one of Einstein’s 300 or so published papers was ever peer-reviewed, which so disgusted him that he never submitted a paper to that journal again. It did not matter that the DNA papers and Einstein’s papers were not peer-reviewed. Nor did it matter for the many thousands of the classic papers published in the past century that were not peer reviewed: the work in them is the foundations on which science stands today.” - The Absurdity of Peer Review (Mark Humphries)

-

“John Deere employs more software engineers than mechanical engineers” - John Deere Turned Tractors Into Computers - What’s Next? (Nilay Patel)

Entrées First

I always do this now:

The Count reviewed the menu in reverse order as was his habit, having learned from experience that giving consideration to appetizers before entrées can only lead to regrets. - A Gentleman in Moscow (Amor Towles)

Photo of the Week

I took this photo last year on the California coast and recently had it framed for my office. Beyond the memories it brings back of the day, I still love how this was like peering into a private moment between the setting sun and the deserted coast, one last bask of warmth before night.