Musings #11

Growth at the Expense of Product

In a prior post, I lamented the state of the modern internet being “a mélange of clunky websites, ads, paywalls, cookie warnings, CAPTCHA’s, 17-step logins, endless passwords, annoying javascript popups, more ads, ad blockers to block ads, and complexity to the point of sensory overload.”

But I didn’t really address why this is happening. No decent company deliberately creates these web/app/etc. monstrosities when they are starting out. So how does a product experience go from good to terrible?

The usual suspects of bureaucracy, regulations, lawyers, poor leadership, and the like all play a part. But these culprits are too vague to be useful, and some products defy this pattern. Instead, there are some more nuanced and worthwhile reasons to explore from a business-building perspective relating to teams and management.

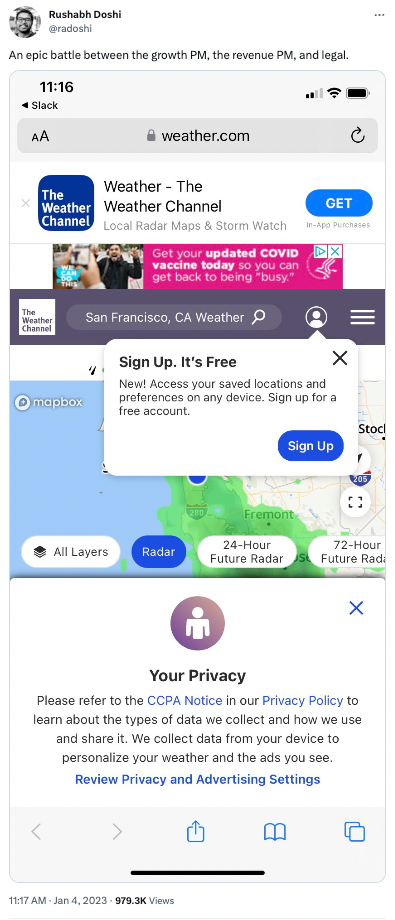

As an example, how does a simple product with a simple function turn into a mess like this?

The viral tweet above astutely describes a battle between legal, revenue, and growth teams (and probably others too). This is exactly what can happen when different functions in a company all get their way without any cohesive vision or care for the user experience. Legal just cares about following (bad) regulations without trying to make the experience better, Revenue might care about something like signups, and Growth is trying to drive app installs because that’s the metric of the month. Meanwhile, no one owns the overall experience.

In other words, different factions are trying to optimize their own short-term metrics that are all at odds with what a good product is.

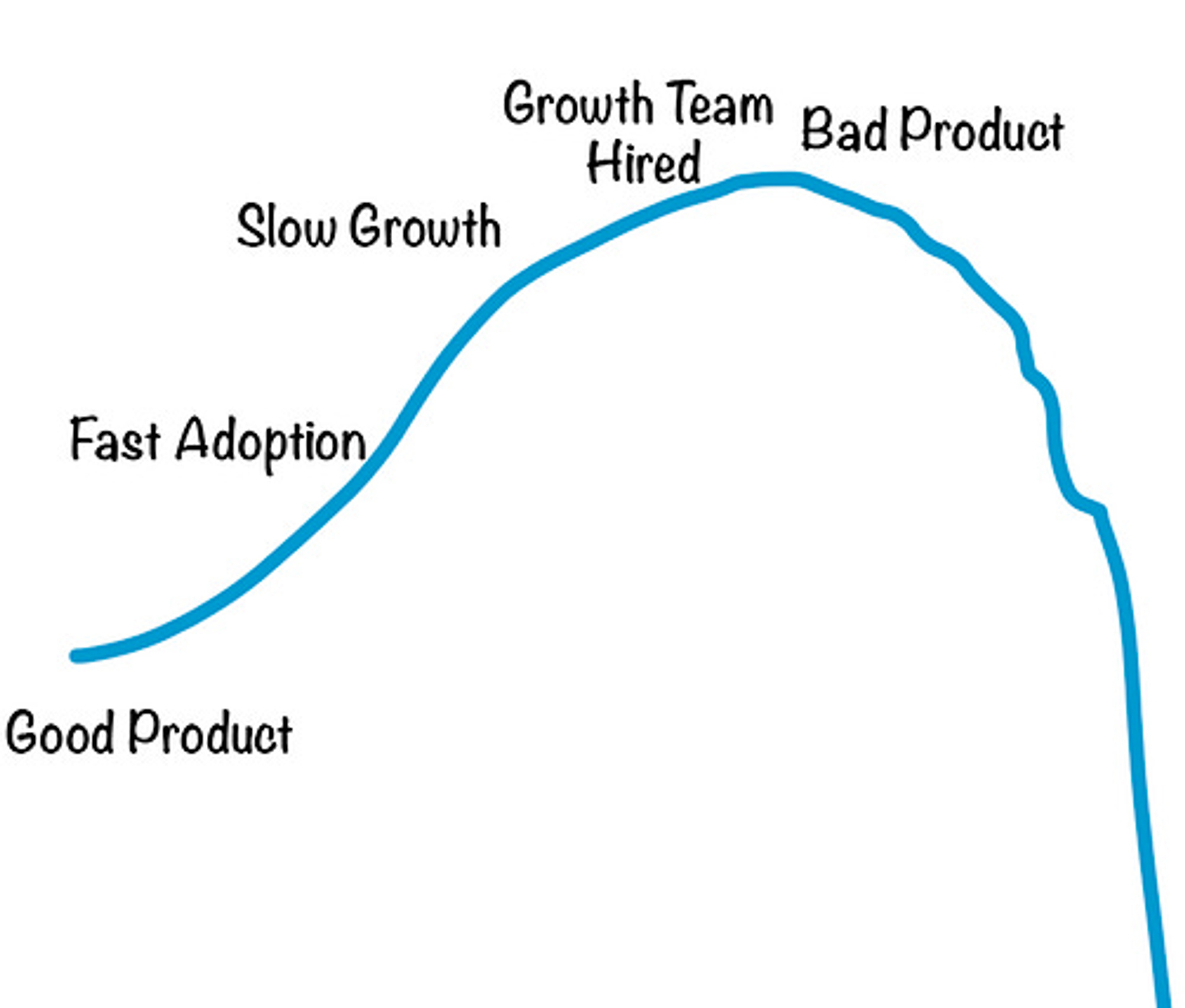

Pedram from the Data Based newsletter recently had a great post called The Trouble with Growth that gets at the heart of why good products can deteriorate specifically when growth teams come in.

What starts as a good product, gains adoption. The fast pace of growth eventually slows due to the laws of physics. Rather than update models and assumptions, the company hires a growth team; they ‘experiment’ and each experiment in isolation seems like a good idea. They might move the metrics in the right direction. Maybe they generate marginal increases in revenue. But the overall experience suffers. And soon, all these marginal improvements end up creating a bad product, which inevitably leads to the downfall.

Source: The Trouble with Growth

Pedrem explains why this happens via some basic but useful statistical concepts including Simpson’s Paradox, Local Maximums, and Anscombe’s Quartet. I recommend reading the post for all, though the most interesting and relevant one is Simpson’s Paradox, which is when a trend for groups of data appears to be moving in one direction, but disappears when the groups are combined.

Source: Wikipedia

The scatter plot is the illustrative representation of sub-metrics a growth (or other) team is trying to optimize, and the overall trend line is the declining product quality.

Add in the conflicting goals of other teams and you have a recipe for the state of most of the consumer web and a lot of other technology products as well.

This isn’t a condemnation of growth as a function - there are plenty of growth teams at companies that have the bigger picture in mind and actually make the product better. The issue is when growth teams are solely focused on a/b testing and experiments to improve short-term metrics that aren’t the north star of the company and/or are at the expense of long-term user experience.

There are other factors, but this explanation gets closer to the heart of why once-great or could-have-been-great products tend to deteriorate in user experience as they mature.

The antidote is easier said than done, but I believe has two parts:

-

A strong product leader/owner who balances the learnings and improvements that other teams can bring with tight control on always maintaining/improving the product quality from a user experience perspective.

-

As Pedrem advises, the founders/execs are responsible for the “what’s next”, before the initial product gets into the incremental win phase.

What they should have been doing was preparing for this scenario months ago. The best founders are always paranoid and never satisfied. They’re less focused on how to win today, but on what to win next.

Thoughtspace

One of my favorite essays of all time is The Release Ratio by Lawrence Yeo of More to That. It is a wonderful exploration of content consumption and the mind’s need for a release valve in the form of creation.

When you consume content, it’s good up to a certain point. It’s great to learn more about the world, but then you must follow that up with: “Okay, so what do I do with all this information?”

If you never act on that question, then content consumption turns into an unhealthy addiction. You start tricking yourself into believing that knowledge acquisition is the end goal. This is when Mr. Podcast, Mrs. Video, and Mr. Book are no longer useful, regardless of how rich in quality they are.

The prescription is getting your creation/consumption (“Release”) ratio to an optimal level.

To make content consumption meaningful, you must create or build something with it. It can be something concrete like a product or a service. It can even be something more process-driven like a habit or culture.

Regardless of what you build, it is this very act of creation that releases the brain fuel inside your head. All the knowledge you have is a store of wisdom, but you will never unlock that wisdom if you never act upon what you know.

This post was a major inspiration for me to write more, and it has helped me strike a better balance.

Recently, though, I’ve realized the creation/consumption ratio is missing an element: thoughtspace. It is not enough to add a bit of creation while still consuming immense amounts of content. Instead, there needs to be separate time and space to think about the things you are interested in; a protected environment to allow your mind to generate ideas and solve problems. Task your brain with the things you want it to do, and give it thoughtspace to work it out.

Thoughtspace is where great ideas come from.

Good ideas require boredom. If you constantly ingest new information, the existing information can never be digested. It’s as if you’re looking at your fermenting jar on the counter every hour and wondering why nothing has happened, so you open it and stuff in another cucumber.

That quote is from Nat Eliason’s phenomenal post entitled The Art of Fermenting Great Ideas, which has been percolating in my head for the last few months (a sure sign of interestingness) and where this notion of thoughtspace comes from. He calls this “output time.”

The ways we fail at this are obvious. We never give ourselves output time because we’re terrified of silence and boredom. We need a podcast while working out. We need music while working. We keep social media up in another tab. We have notifications on our phones. We let ourselves be interrupted.

If your first response to boredom is to seek out another input to sate the longing for stimulation, then your brain never has to make shit up to entertain you. The idea muscles will atrophy and never produce anything of worth. But if you can respond to boredom by leaning into it, keeping the blank page open, and seeing what pops out, the muscle gets stronger over time.

There is a reason great ideas often come from “shower thoughts” or from sleeping - these are rare times we aren’t inundating our minds with new information.

The easiest and most effective practical change for me has been to stop listening to music or podcasts while driving or working out, and instead, just think about focus areas and let my mind wander. Simply taking short walks sans phone works wonders as well. I’ve had so many great ideas and problems solved this way.

Nat has many great insights in the post relating to idea generation - worth the read in full. Some other key highlights for me:

Every tweet you read, every newspaper you glance at, every show you watch, every email you skim, it’s all feeding your subconscious things to process. And whatever it’s fed, it will ferment into ideas and reactions. So if you want to come up with better ideas, you must get extremely strict about what you let in the door.

Ideas sometimes seem to need days or weeks or months to get to a point where they feel fully formed. If you try to force a solution to a problem into a preset window of time, you will almost certainly reach a suboptimal solution.

Hard

This is a gem. I like this a lot. Good for parenting, too.

Curveballs

-

“If a company is serious about building for the long-term, the Rule-of-40 operating model - as currently implemented in public markets - must be destroyed. Don’t let its simplicity deceive you. It’s capable of compelling executives into decisions that ultimately destroy long-term value and prevents them from building the enduring organization they truly desire.” - Lord of the Operating Models (Mike from NonGapp)

-

“So I was really asking from an existential standpoint whether these kids were lucky. Usually what would happen is that I would ask, “Are you lucky?” And they would answer, “Well, I think I’m lucky…” and I would correct them and say, “No, I didn’t ask if you thought you were lucky, I asked if you are lucky.” At this point they would be totally stuck, trying to figure out the answer that I was looking for, and trying not to bomb out of the interview. 90% of the interviews went this way.” - Are You Lucky? (Jared Dillian)

-

“Within a gallery, a piece is valued based on its lineage, its originality, and the trials and tribulations of the artist. A replica of a priceless work is worth nothing. “This was created by Generative AI model X based on Y text prompt” is a pretty lackluster and uninspiring story, much like “This was painted by X as a replica of a masterpiece painted by Y.” Who cares? So, if the story defines the value and respect for a work of fine art, why wouldn’t the premium of story carry over to other creative genres, especially in a world where anyone can generate anything with a text prompt (or print a replica with a printer)?” - Creating in The Era of Creative Confidence (Scott Belsky)

-

“The less you know of the measurer compared to the thing being measured, the less the measurer’s measure measures the thing being measured and the more it measures the measurer.” - 10 Ways to Avoid Being Fooled (Gurwinder)